A few weeks ago I read a book called Shop Class as Soulcraft by Matthew Crawford. It has the audacity to suggest that work our society tends to undervalue, the kind that often involves dirt and sweat, is actually good for the soul. The ideas in the book are compelling, so let’s explore them.

photo from flickr.com/hiddenTreasure

Before going further, let me apologize for the length of time since my last update. In addition to my day job, I’ve got a role in a play, and I’m working on another creative project that I am racing to finish. I’m also developing some other stories for this blog that involve more research. I still care about those of you who trust me with your time by reading my posts, and I want to get better at posting more consistently. I mention this because I value transparency and because I don’t believe in the idea that a good worker is by definition as consistent as a well-oiled machine.

Pursuing excellence in challenging fields can sometimes involve months and even years of training and experimenting with little apparent progress. Nassim Nicholas Taleb makes a compelling case for valuing that kind of unpredictable work in his book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. It’s a good book to read if you care more about long-term achievement than about short-term benchmarks.

photo from flickr.com/a-mon

photo from flickr.com/a-mon

These scene kids might think you’re cool, but that’s not going to persuade your broken car to start.

By the time he opened up his own repair shop, Mr. Crawford had sanded away any desire to ever return to his old information-driven job. That doesn’t mean he now disdains knowledge. Quite the contrary. His book references philosophers, prominent research, and current events. Besides, the book itself is an engaging, enjoyable read, and you can’t write that kind of book if you don’t take some delight in organizing information. It was the facade that his job induced, the pursuit of meaningless metrics and half-truths, that drove Mr. Crawford out of the think tank.

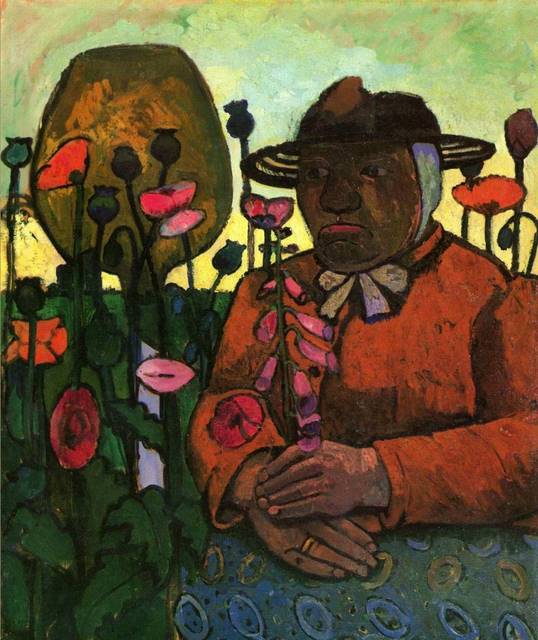

photo from flickr.com/chrysti

The emphasis is on learning general skills that can someday be applied to specific situations, someday but not any time soon, because, Mr. Crawford explains, our society doesn’t want to limit a child’s possibilities. After all, suggesting that it takes time, effort and focus to become a master at something might hurt someone’s self esteem. Is it any surprise that the old, but highly-effective, practice of having a master train a young student as an apprentice has become almost non-existent in our society?

Let’s not forget about the social stigma of vocational classes offered in school. When I was in school, there was this sense that vocational classes were for those weren’t good students and who weren’t going to college. Maybe that very mentality explains why so many schools are cutting back on their vocational programs.

Based on my own educational experiences and those of friends and family, I conclude that knowing the stages of photosynthesis is an essential quality of a good citizen, but being able to fix things, either as a job or as a service to the community, doesn’t matter very much. During my school days, I learned about photosynthesis in one mandatory class after another, but I never learned how to build a shelf. I can assure you that I’ve never run into a real-world situation that made me think, “ah hah, that’s the effect of the Calvin-Benson Cycle at work!” In contrast, there have been several times in my life where I wanted to build something, but I didn’t know how.

photo from flickr.com/danstrange

Striking a more optimistic note, Mr. Crawford reminds us that the do-it-yourself sensibility is growing, even though this sensibility doesn’t always make economic sense. For most people, buying the raw materials and then building a sofa costs more money and takes longer than just buying an affordable sofa from the furniture store. And yet, a certain number of people still choose to make their own furniture. These folks aren’t fools. They just appreciate the inexplicable sense of pride that comes from crafting something useful with their hands. It may not be good for the bank account, but it might be just what the soul needs, at least that’s what Mr. Crawford wants us to conclude.

When I was growing up, I got caught up in the whole information thing. I would cram facts into my head not because they were useful but because they might help me get a better grade on a test. Only after I tried to build meaningful relationships and seek significance beyond the classroom did I realize that there is more to life than just knowing the right answers.

Sometimes the doing is more important than the knowing, and you don’t have to be a mechanic to appreciate that. Does that mean working with your hands will save your soul? Well not necessarily, but maybe it’ll keep you humble and out of trouble for a while, long enough for you to hear the things that God wants to whisper to you. I can’t speak for your experience, so I’ll talk about mine. If I can get myself to just show up ready to do my best, create and listen, then I have a better chance of prevailing against the self-destructive inclinations that encroach upon the day.

Am I extending the metaphor too far? Perhaps, but consider this: Jesus was a carpenter, and Stalin was a politician. Curious details, don’t you think?

photo from flickr.com/cobalt