“Too many rules prevent accomplished jazz musicians from improvising, and as a result they lose their gifts, or worse, they stop playing altogether.” That’s a quote from Barry Schwartz’s fantastic speech on our society’s loss of wisdom. (It was a speech given at this year’s TED conference, and I highly recommend watching it.)

It’s sad isn’t it, when our jazz musicians, athletes, unique thinkers, visionary entrepreneurs, volunteers, and all the others who strive to bring more meaning into the world experience something that causes them to forever stop doing what they do. Too often the villain responsible is a corporate one, a thing that could have been avoided with a thinking mind and a working heart.

The death blow doesn’t always come from the heavy artillery. Sometimes all it takes is a phone call. Please allow me a personal story: it’s why I had to write this post. With just one five-minute phone call, a producer that I’ve been in contact with for over seven months almost shattered my inclination to ever create again. He did this not by denying the merit of my project, something that I’ve been working on for the past few years of my life, but by telling me that after 7 months he hadn’t gotten to read it yet because his time was very valuable.

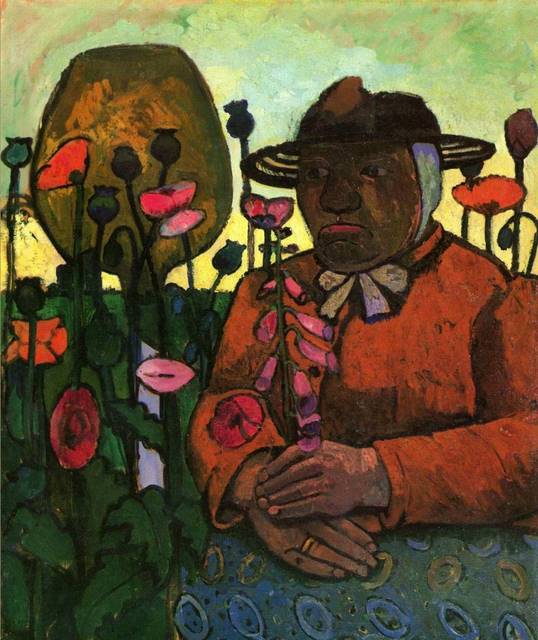

Old Poorhouse Woman with a Glass Bottle - Paula Modersohn-Becker

I sent him 11 pages to consider, and yes folks, that’s 11 pages and not 110. Before I did that I saw his shows and read his book to better understand him and to determine whether my project could possibly be relevant to him. I thought it could be, but I assured him that I would not call or email him again if he gave me a definitive no. A “no” he would not give me, but a declaration about the value of his time, he freely shared.

I shut down as a person for almost a week because of that. I got little done, and I wasn’t the easiest to be around. Because of him, I thought seriously about just settling for a life of doing corporate work and spending money to buy more comforts and pleasures. Thank God, I no longer feel that way.

I’m not writing this to lash out at him in public. That’s not my style. I prefer to settle my disputes with someone person to person, and as God is my witness, he will know what I think of his actions, and I will get a definitive yes or no from him, or I will die trying.

My point is that sometimes even seemingly small, thoughtless moments can perpetuate a more corporate world. The producer in question is not altogether bad man. He is in many ways, I’m sure, more decent than I am, but he almost convinced me to give up entirely on pursuing any kind of creative expression, the very stuff that gives my life the strongest sense of purpose, harmony, and hope. Put differently it’s part of the least corporate elements in my life.

I recognize the very real possibility that I have done or could do to someone else what he almost did to me. This list, inspired by Barry Schwartz’ lecture, is my way of fighting that possibility:

1. Take strong positions.

If you’re not interested in a project, why tie up someone’s time by being ambiguous? By saying an honest no, you make it easier for someone to turn his attention to more rewarding possibilities. Certainly, it can be uncomfortable to say no and face the disappointment or frustration of another person, and besides, staying undecided for as long as possible is convenient. Unfortunately, with your ambiguities and your delays on a decision, you add your own home-made resistance to someone else”s dreams, and dreams are hard enough to bring to life without your half-hearted opposition.

Barry Schwartz isn’t vague about what he accepts and what he doesn’t. That’s one reason why he’s compelling. Corporate speakers, though, are too concerned about saying the wrong things, so they hedge. To prevent you from realizing this, they distract with mesmerizingly awful PowerPoint animations. No one enjoys hearing those people speak, but everyone claps out of habit.

Speaking of PowerPoint presentations, you’ll notice that the slides Mr. Schwartz uses have an elegant, minimalistic design. The ideas are strong enough on their own so that cutesy, animated gifs aren’t needed to hold the audience’s interest. (To read more about the thinking behind the slides for the presentation, check out this helpful lessons-from-TED post from slide:ology.) If your presentation isn’t compelling enough, maybe you should spend more time tweaking your ideas and not your clip art.

2. Avoid meaningless clutter.

I am amazed by how many companies choose to use hold recordings that go something like this, “Thanks for calling. Your call is very important to us. It will be answered in the order in which it was received.” This is something any company can say. Is your company just like any other company or does it have something special to share with the world? Your advertising says that you are special, so why let your phone messages or your internal training videos, or your memos argue otherwise?

As if the above phone message isn’t bland enough, too many companies opt to have the message repeat every 45 seconds or so. Right when I am getting comfortable enough to start daydreaming about new possibilities, I get interrupted with generic words from a generic voice. That’s sort of like throwing balls of Styrofoam at patrons right when they’re bringing a spoon of hot, savory soup to their mouth. That kind of thing robs me of my appreciation for the moment, a moment that could have begotten good and useful things.

Why waste words to apologize for the inconvenience when it really isn’t an inconvenience? Asking me to use a different grocery-store isle because the one in front of me is closed is not an inconvenience. It is a reasonable situation that common sense illuminates. Using plastic phrases on me rarely makes me feel better, and clunky legalistic prose doesn’t encourage me to spend more money. When I discover it in stuff I’ve already purchased, I have fewer reasons to smile about the product in question.

As Mr. Schwartz suggests, there’s no reason for teachers to read the lesson from a script. That insults the competent teachers and bores the kids. If the teachers aren’t able to come up with their own coherent lesson plans that address relevant topics, then they should be doing different work. Making things easy for incompetent people to be mediocre has the unfortunate consequence of making the world more corporate at an exponential rate.

3. Incubate possibilities.

Both babies and new ventures cannot survive on their own without support from others. The call that you don’t return could be the one that seduces someone to give up on something that would have changed the world. One of my goals is to return a call or email that asks for a response within 2 days. I’m pretty good at doing that most of the time. If I can do it, why can’t you? Why risk the chance of demoralizing someone when returning a personable call usually takes just five minutes or less?

Barry Schartz warns us that if people have to swim against the current for too long, they’ll give up. Some ideas don’t have enough merit to justify their survival, but others do. It’s tragic when the good ones get strangled by the organizational resistance that attack with bureaucracy and mindless adherence to policy.

4. Avoid unnecessary rules.

To quote Mr. Schwartz again, “Moral skill is chipped away by an over-reliance on rules that deprives us of the opportunity to improvise and learn from our improvisations, and moral will is undermined by an incessant appeal to incentives that destroy our desire to do the right thing.” The more rules you make the more you encourage the rise of corparate drones who merely follow policy and don’t think or interact with the particulars at hand. Those kinds of workers can be crafted into docile automatons, but they won’t be very good at generating innovation and adapting to change.

5. Don’t be cynical.

Everyone has their shortcomings, but we sell people short when we search for base motives behind every deed. Treating others with weary suspicion even when they do good makes it harder for that person to continue doing good. I’m as guilty of this as anyone, maybe even guiltier than most; I face an on-going battle against encroaching cynicism, and I don’t always win.

When you’ve been hurt, it is a challenge not to project those past experiences of cruelty and selfishness onto other people in the present. But, if you keep treating an organization or a contact with enough cynicism, eventually they’ll ignore you or live up to your expectations. Neither party benefits from that, so that’s reason enough to keep a vigilant guard against corrosive cynicism.

Follow Mr. Schwartz’s advice: “celebrate moral exemplars.” Dare to praise others not just for their technical capacities but for the nobility of their actions. You may risk looking unsophisticated, naive, and unhip, but do it anyway. Virtue matters enough to justify the risk.

6. Be honest.

Well-intentioned buisness people are, on ocassion, hesitant to speak the truth out of fear for the market’s reaction or their jobs. On a personal level, people are hesitant to tell the truth out a fear of rejection or of the consequences that come with the truth. These are not petty matters to be easily dismissed.

Sometimes being honest will cost you in the short term, but it comes with long-term freedom, freedom to be yourself and to make decisions based on what can help you or your organization grow. In the end, honesty always prevails, but you won’t believe that unless you accept a metaphysical reality greater than the perceivable material, and often very corporate, world around you.

If your worldview does not allow for a God or a universe that ultimately rewards character over profitability, then there is a very real danger that you will end up as another corporate denizen who will do anything to stay on top, perhaps you’ll even apologize for the inconvenience as you uppercut me with your meaningless clutter. Anything to stay ahead, right?

Photo from flickr.com/rickz

Here’s me being honest: I had decided against writing this post, until I came across Barry Schwartz’s speach. The beauty of his ideas helped snap me out of my own private hell, long enough to write this. Whether this post will be helpful to anyone, I don’t know, but writing it was helpful to me. Before watching Mr. Schwartz’s speach, my plan for the weekend was to spend much of it drinking one beer after another at a local bar. By being less corporate, Mr. Schwartz helped me to do the same.

You can do likewise, if you’re so inclined. Somewhere in the world a jazz musician will thank you.

If this article has been valuable to you, consider adding a comment or sharing this with a friend.

I’m glad you wrote this instead of drinking beer, because it meant something to me.

And in defense of my sometimes lengthy delay in returning calls – most conversations I have last upwards of an hour, so the five-minute-returning-of-the-call-for-the-sake-of-returning-the-call is not satisfactory.

Hey Ben,

Thanks for your continued support.

I can assure you that I wasn’t thinking of you when I wrote about people not returning calls. A conversation with the great Ben is not something to be rushed but something to be savored, and so I am grateful that when we do speak we can do so for a prolonged period of time, instead of doing a quick word burst. As you may have noticed by now, I’m a long-form kind of guy.