If you wish to carve out a corporate existence for yourself, you will probably avoid showing others a new way of seeing something. Doing that is risky, unproven in profitability, and more conflict-prone than the old tried-and-true methods approved by the powerful and the influential. Corporate fellows avoid the above-mentioned adjectives in the same way that unrepentant alcoholics avoid AA. (This applies even to the indie-rock scene kids who slavishly follow the fashion dictates of their hipster overlords in the name of assimilated nonconformity.) Malcolm Gladwell is not one of those fellows.

Les Saltimbanques at the Races - Picasso

In his book Outliers, he challenges the idea that someone’s success is determined almost exclusively by his or her own efforts. Mr. Gladwell still argues that individual effort matters: he insists that successful people need about 10,000 hours of practice to become masters of their craft. Still, the book spends more time discussing the role society plays in encouraging and nurturing the success of outliers, the superstars in their fields who are exponentially mre skilled than their colleagues. That kind of non-conventional thinking makes the book worth reading, but I want to focus on a specific quote from the book that hasn’t been as widely discussed.

Here’s the quote: “Autonomy, complexity, and a connection between effort and reward are the three qualities that work has to have if it is to be satisfying.” If there is a better way to describe an uncorporate job, then I haven’t heard it. As it happens, it’s also a helpful framework for discussing great design.

Few things deaden my enthusiasm for a job more than an employer who tells me exactly how to do my work. Yes, every business and design assignment has its standards and protocols. Nothing wrong with that, but why insist on making me or my coworkers read from a script or do things exactly like you do? Machines need to be micromanaged, competent people don’t. Instead, why not tell us what results you want, give us some flexibility in pursuing those results, and reward those of us who best achieve those results?

One of my worst experiences on a design job involved a client who wanted to tell me exactly what elements I should use for a poster and where they should go. I don’t mind that kind of thing if a client has design instincts that are as good, if not better, than my own, but that was not the case with him. He relished the clip-art aesthetic. I’ve had enough of those experiences that I now reserve the right to refuse to do work that I find ineffective in conception. The customer is not always right, and life is too short to do ugly design.

Designers, artists, and employees in general have their own unique perspectives and abilities that they desperately want to share with you. Why not seek to discover and use those abilities to your advantage, so that you can accomplish whatever specific tasks need to be done? You’ll get more interesting and more valuable results while keeping your employees more engaged. I understand there this a place for procedure. Deviating from it can involve some experimentation, and not all experiments succeed. Still, the potential for discovering a friendlier, more appealing, more efficient, more profitable way of doing things, seems to be worth the risk, don’t you think? Not convinced? Well, which would you rather have in your house: a Picasso painting or a generic photograph with a caption about corporate excellence?

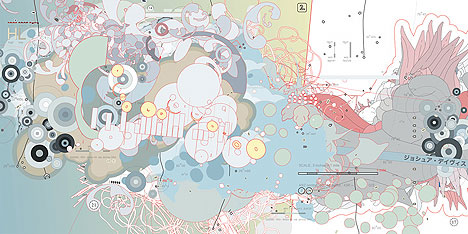

Maxalot - Joshua Davis

Take a look at the above design by Joshua Davis. This kind of visual complexity is something in which he specializes. Maybe you’ve seen some of the ads he’s done for companies like Motorola? (If you like his style, you can see more of his work at joshuadavis.com.) In any case, is there not something compelling about this kind of complexity? We are inclined to look for patterns in the complex, to discover a sense of order and harmony that transcends the chaos in our world and gives it meaning. Too much complexity is an overwhelming, frustrating experience, but without enough of the stuff, we lose interest and don’t stay fully engaged. No wonder Mr. Gladwell sees it as an essential ingredient in fulfilling work.

You could also say the same thing about a good design, which is after all, a pleasing arrangement of complex elements that serve functional or aesthetic purposes. Too simple a design conveys half-hearted apathy. On the other hand, if you add too much complexity, then you produce something that interferes with its own functionality. To pull off this balancing act with elegance and style is the real trick of the thing.

And now we get to the connection between effort and reward. Notice that Malcolm Gladwell did not say the connection between effort and the amount of money earned. It’s a pernicious corporate assumption that everyone does things simply for more money. Some people just want to see that their efforts earn them respect or affection from others. Whatever the payoff may be, people want to see it come eventually, or they’ll stop working as hard or stop working altogether. From a designer perspective, that means users may give up on a product, protest a policy, or ignore a poster that demands too much effort or attention without giving back enough rewarding functionality.

The volunteer who helps out at her church probably doesn’t want money for her efforts. And yet, if she continues to give her time to serve others but gets no appreciation or sense of making a difference in return, she will probably stop helping at some point.

The local actors I know don’t care so much about getting paid big bucks or becoming famous (at least not all of them), but they do care very much about giving performances that are well regarded in meaningful productions. They also care about connecting with other actors and earning their respect. Taking away those things and you could jeopardize their future dramatic endeavors. I’ve done a little bit of acting myself (I’m not a great actor, but I enjoy learning and going through the process), so I know how hard it is to face rejection after rejection without hearing, on occasion, about how someone was affected by your performance, big or small.

Conversely, if you want the world to be a less corporate place, be sure to pay people for the efforts that bring you satisfaction. One of the owners of the Boot, an Italian restaurant in Norfolk, Virginia known for a vast beer selection, hearty meals, and great music, told me about his visits to a nearby, upscale comic-book shop called Local Heroes. He aims to buy something from the store every few weeks, because he believes the area deserves a place like that. I feel the same way about the Boot. I want to reward them for their efforts, so that they will continue to find satisfaction from staying in business.

Support the things you cherish with money if you can, but an honest, heartfelt thank-you is cheaper and sometimes more appreciated. Comments on this blog have helped me see that others value my efforts, and so I continue writing, instead of merely looking for more ways to make money. On some difficult days a few kind, thoughtful, or grateful words have made all the difference to me. Knowing this, I look for every opportunity to offer a sincere and unique expression of gratitude to others whose efforts I appreciate.

Find ways to include autonomy, complexity, and a connection between effort and reward in the work you do, the work you ask others to do, and in the things you create, and you’ll be doing your part to make the world a less corporate place. (By the way, thanks for reading this. I really appreciate it.)