In case you’re wondering, the title was inspired by a comment that Andrew Stanton made on the DVD extras for Pixar’s A Bug’s Life. He was explaining that their movie involved so many technological marvels that it should be released as the super-genius edition. I hope Mr. Stanton won’t mind too much that I borrowed his phrase to celebrate his company.

If the title did not already make this point abundantly clear, I have no intention whatsoever of writing an unbiased, scientific-sounding piece on Pixar. You see, I am very much biased in favor of the company. Pixar was one big reason why I dedicated a few years of my life to the study of computer animation. (There was also a fairytale and a girl, but that’s a whole other story.) I don’t have a successful career in that field as of yet, and even if I never do, I’m certain that when it ends for me here on this earth, Pixar will be one of very few companies that had a defining impact on my life. That’s worth writing about, don’t you think?

Photo credit: flickr.com/thomashawk

You know what else is worth writing about? Going 10 for 10 in box office hits. Every single movie that Pixar has made achieved enormous financial success. Name another company, whether film or otherwise, with that kind of track record. I can’t think of any.

If a company can produce one hit after another in a competitive industry where failure is, according to the statistics, the expected outcome, then there must be some magic in the web of it, as our friend Shakespeare might say. I wanted to learn about that magic, and so I began to study the company.

I’ll mention a few references at the end that go over the history of Pixar and some of their interesting business practices, but I’m not going to rehash all that here. I’m more interested in trying to get to the soul of Pixar by looking at the work they’ve produced. After all, you can know the history of a person without really knowing who he or she is. Companies are no different.

To prepare for this admittedly daunting task, I re-watched every single Pixar DVD, including the shorts, commentaries, documentaries and all the extra features. I have also read and listened to books about the company as well as technical discussions that Pixar employees have given at places like Siggraph, Computer Graphics World, fxguide, and so on.

The movies, though, are the essence of what Pixar does, and that’s where I’ll concentrate. With that said, let’s dive in!

It’s Not (Just) About the Benjamins

“If we had approached this only from the standpoint of marketing, maybe this movie would not have been made. But that’s not what interests anybody at Pixar. What interests us is, Does this sound like a great story?” That’s Brad Bird, the director of Ratatouille, talking about his movie with Entertainment Weekly. Now that he mentions it, I guess rats handling human food is not the most obvious concept for a blockbuster.

That’s not the only time that Pixar avoided the obvious route. Wall Street analysts predicted that Up would hurt Disney’s profits because it did not have any compelling characters that make for good action figures.

Not enough people would pay money to go see an action-adventure cartoon about an old man in a house, they snidely insinuated. Pixar won the argument by creating a crowd-pleasing, Academy-Award-winning film that made us care about a type of character who is normally ignored in cinema.

Even though kids make up a significant part of Pixar’s audience, the filmmakers behind Up resisted the temptation to over-explain. Instead, they tell the story of Elie’s death almost entirely in montage, and it’s one of the best montages in recent film history.

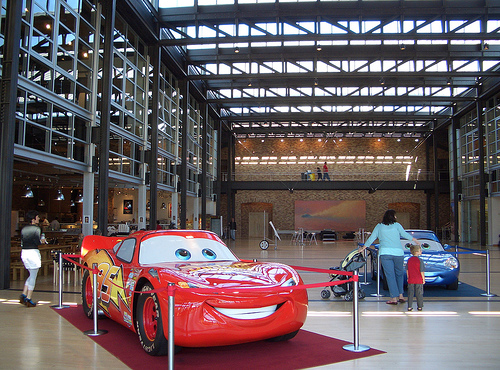

Sure, that took longer to do and cost more money, and you don’t have to work that hard to keep most kids engaged. Still, Pixar goes the extra mile. They budget trips for their production people in the name of inspiration: For Cars it was a roadtrip across the country. For Finding Nemo it was scuba-diving in the ocean. On Up, they flew in their artists to a remote location in Venezuela by helicopter.

Every Pixar movie comes with at least one short and a few documentaries. When the company is feeling particularly generous, you also get games, short-stories, Easter eggs, and fun character-gag reels.

These extras take months of time to produce, and yet most people would still buy the Pixar movies without them. With all the added value that they offer in their productions, you would think that Pixar would charge more for their movies, but they don‘t.

Photo credit: flickr.com/adrianhon

As it turns out, 4 of the 10 Pixar films have plots that question the pursuit of profit for merely the sake of profit. In Cars, the driving motivation for Lightning McQueen is getting the Dineco sponsorship. He literally drives across the country to get it, but when he learns to care about others he realizes there are more important things in life than getting the right sponsor.

In WALL-E, the humans have devolved into consumer blobs in part because the company Buy N Large encourages them to buy lots of things as often as possible. If you’ve ever had to work with just-make-the-bar-graph-go-up types, check out the Buy N Large featurette on the WALL-E disc. It might make you laugh or cry, depending on how close it is to your experience.

Remember Monsters Inc? That’s about a company struggling to make bank by scaring kids. The owner Mr. Waternoose complains that it’s getting harder and harder to scare kids, so he partners with the bad guy to make a more sinister scare extractor.

When Sully and Mike Wazowski realize that laughter is more powerful, more profitable, than screams, they transform the entire company’s business practices. The workplace appears drab and lifeless when scaring is the goal; when laughter reigns, the environment becomes one of celebration.

A company that makes money by scaring people: what might that represent? I don’t know. Hmm. Could that be … Hollywood? There are definitely movie companies who are ready to do anything to make a quick buck, even if that means debasing human dignity and pandering to people’s basest instincts.

Pixar, though, has had enormous financial success without resorting to the use of strippers, gruesome mutilations, and f-bombs. They’re such capable storytellers that they don’t need those things to keep an audience engaged. Do you know who isn’t that versatile? David Mamet!

(Yeah I said it. Mr. Mamet does write interesting plays, but it would be nice to see him expand his vocabulary beyond the f-word, the beloved colloquial variations of a man’s reproductive organ, the thesaurus entries for ‘scheme,’ and the cosmopolitan variations of ‘money.’ Hey, Shakespeare didn’t have resort to swear words every 12 seconds to sustain dramatic tension, so it is theoretically possible to do even when writing a play.)

There is value in exploring the darker sides of human life, but dramatically that’s sometimes the easy way out. Besides, what if that exploration encourages corruption in others and makes society worse as a result? Is it worth it? I don’t know. I wrestle with that question as a writer, as a moviegoer, and as an imperfect person who aims, but doesn’t always succeed, at living a good life. But just because a question is difficult to answer, doesn’t mean it is not worth asking.

Anyway, back to Pixar. One of my favorite scenes in Monsters Inc comes when Sulley sees the devastation that his scare tactics have caused his now cherished little Boo. He tries to explain that he is just doing his job, but Boo doesn’t understand that. All she knows is that someone she once trusted caused her pain.

In that moment, you can tell that Sulley is starting to question the things he does just to turn a profit. If only more people in this world would do that.

Photo credit: flickr.com/sutekidane

Let’s go back to Ratatouille. One of the bad guys in that movie is Skinner. He’s taken over Gusteau’s once great restaurant and is trying to squeeze every dollar out of the brand by coming up with derivative products like frozen, microwavable burritos. Yeah, that’s kind of like … what was it again? Oh yeah: Disney, when they were looting their own classic film library and cranking out direct-to-video sequels that suffered in quality.

Supposedly that’s what Disney tried to do to Pixar when profiteer-in-chief Michael Eisner was running the Mouse House, and if my history is correct, the Pixar-Disney dispute was happening around the time that Ratatouille was being developed. Coincidence?

A Family that Plays Together

Another thing about Pixar that’s hard to avoid noticing is how comfortable the employees are around each other. In one DVD after another, the directors are seen joking around with the writers, producers, and animators.

Think that’s no big deal? When was the last time you shared a laugh with Jim in accounting? If you are Jim from accounting, when was the last time you had a bonding moment with Steve from IT?

Most of the time, big companies are broken up into separate departments and those departments rarely interact with each other, at least not in any meaningful way. “Did you get the memo?” does not count.

Photo credit: flickr.com/oldpatterns

Not so at Pixar. For one thing, their building was specifically designed by Steve Jobs to encourage random interactions as people walk to their desks. Also, let’s consider Pixar’s operating principles. Two out of three involve collaboration. Here they are:

1. Everyone must have the freedom to communicate with anyone.

2. It must be safe for everyone to offer ideas.

3. We must stay close to innovations happening in the academic community.

Isn’t it interesting that a company so dependent on bleeding-edge technology doesn’t list technology first? That’s because Pixar puts more emphasis on finding the right people than on finding the right ideas, as Ed Catmull re-iterates in one interview after another. (Of the original Pixar founders, Mr. Catmull is the technical genius. Steve Jobs is the business wizard, and John Lasseter is the chief creative.)

It’s not just about finding the right people. It’s also about making sure that they work well together as Pixar’s HR executive Randy Nelson explains. Adding the right person to the team should be like adding 1 + 1 to get 10.

If all this talk about the value of people was just standard HR corporatespeak, then there’s no way that you would see the casual spontaneity between the artists in the documentaries.

Being in a stressful environment with a very talented, but very opinionated, group of artists is not a surefire way to attain happy-go-lucky bliss. Just ask anyone who’s ever worked on a film or a play. Yet somehow Pixar has woven a sense of camaraderie into their culture that overcomes the strain of production.

The culture of playfulness is key. At Pixar, there are games and dress-up days. The animators elaborately decorate their cubicles in whimsical styles, and even the boss gets in on the action. Although John Lasseter is one of the most powerful men at Pixar, he has no qualms about conducting interviews in his toy-covered office. You can see pictures of the fabled office at imagineeringdisney.com and julesbianchi.com/blog.

I don’t remember when I first saw footage of John Lasseter’s office, but it made quite an impression. It’s the reason why my cubicle looks like this:

I figured if it’s OK for Mr. Lasseter to surround himself with child-like things that inspire him and make him smile, why should I worry if people think my desk is a bit different from that of the typical employee at Canon? Seeing little reminders of things that matter to me is sometimes enough to get me through a long day. As an added bonus, management avoids my desk when giving bar-graph powered tours of the building.

Speaking of management, the Pixar guys bring their playfulness even to the meetings they have with their bosses. In particular, I’m thinking about the Fleabie bit they did to show the Disney people what they were doing, at a time when a lot of the executives didn’t understand the computer animation process.

Instead of doing a PowerPoint presentation, they partnered a flea puppet with John Lasseter, who does an impression of a Japanese actor dubbed in broken English. Oh that Lasseter, such a ham, but who wouldn’t want to have him for a boss?

Not Too Big to Fail

Failure is not an enjoyable topic to discuss. Most folks prefer to talk about how unconditionally awesome they are. Pixar is 10 for 10, so if anyone has earned bragging rights, it’s Pixar. Yet, that’s not what Pixar does. They make it sound like catastrophic failure is just around the corner, and they have to do everything conceivable to avoid it.

“Every Pixar movie at one time was the worst motion picture ever made” John Lasseter explains to Entertainment Weekly. What a humble thing to say for a company that repeatedly does 100 million dollar business. Note too that fresh off of their triumphs with Toy Story 2 and Monsters Inc, they brought in Brad Bird, a Pixar outsider, to direct The Incredibles. They explained that decision as a way of avoiding complacency.

When speaking with Variety, Mr. Lasseter even suggests that making it safe to fail is a critical reason why the company prevails. Doing a speech at Stanford’s business school, Mr. Catmull reiterates that success hides potential problems that need to unearthed. On the WALL-E extra features, Andrew Stanton explains that only if Pixar management doesn’t” see you fall off your bike, then they get nervous.”

Do you get it? This is idea is so hard-wired into the company that it surfaces everywhere you look.

Photo credit: flickr.com/tim_norris

To give a sense of how far this kind of thinking goes, consider the Incredibles DVD. They show you their hair and cloth tests that went badly, and they do it with a laugh track. My computer animation capabilities are nowhere close to those of Pixar animators, but I can tell you that when you are up late for several nights in a row working on a shot that doesn’t come out right when rendered, laughing about the situation is not the default response.

Instead, violence against the treacherous machine starts to seem very appealing. No, I’m not a domestic computer beater, but I have called it some vicious names, for which my computer might require long-term counseling. (See, I did learn something from David Mamet’s plays!)

When Pixar can laugh while showing us mistakes that probably cost them weeks of time and thousands of dollars, we can conclude that failure is a familiar enough concept that the company is entirely comfortable with it.

If They Only Had a Heart

All of these things are incredible qualities, but if Pixar didn’t consistently use technology to touch our hearts, I wouldn’t care. Yet I do end up caring, about toys, and monsters, and robots, and grumpy old men.

When you’re dealing with something so technical, you have to pour a lot of love into it, otherwise the sentiment gets lost in translation. To paraphrase the Apostle Paul, if you show all kinds of marvels on screen, but have not love, your film is just clanging sounds and flickering celluloid.

I’m convinced that the core Pixar creatives are not just extremely talented artists but also people with extremely big hearts. You see it in the way Andrew Stanton discusses his film WALL-E, how it’s really about the way love conquers our rational programming, or when he explains that the idea for Finding Nemo came from a moment with his son: Mr. Stanton was so busy trying to protect and educate his son that he missed the chance to just enjoy his company.

Photo credit: flickr.com/seandreilinger

Or consider John Lasseter. As he was reaching the height of his career, he took a year off and spent the time traveling with his family. He did that after his wife warned him that if he didn’t slow down, he might wake up and discover that his kids had grown up without him. From that experience, he developed Cars.

If you want to make something that isn’t a soulless product, you have to put a bit of yourself into it, sometimes even the parts that hurt. That’s not easy to do, but the Pixar guys aren’t afraid of doing that very thing.

I work hard at what I do. Sometimes it means I get very little sleep, but so far, I haven’t made the progress I’d liked to have made made. That kind of thing can sting if you let it get to you. That’s another reason why I’m grateful for the Pixar films. They remind me that there is more to life than getting the stats or being the top toy, that being excellent at what you do is important, but it’s not nearly as important as caring about the people in your life, and that the seemingly mundane moments of life can be just as meaningful as the fantastic ones, if your heart is in the right place.

In the Toy Story 2 featurette, John Lasseter tells a story that almost brings him to tears. He’s at the airport, and he sees a kid waiting for his dad. The boy has a Woody figurine that he’s proudly holding, waiting with anticipation for the chance to share something special with a father that he hasn’t seen for a while. To John Lasseter that’s proof that the characters don’t belong to him anymore, and that’s reason enough for him to keep making great Pixar films. You don’t react like that if you don’t care about your audience.

It’s that kind of affection that makes me go and watch every single Pixar film that comes out. I can’t say that about any other film studio. Like the kid on the tricycle in The Incredibles, I’m waiting around for the next Pixar movie, because I want to see something amazing once again. To infinity and beyond, Pixar!

Pixar resources:

How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity (a feature in Harvard Business Review written by Ed Catmull)

splinedoctors.com (animation tips and podcasts from Pixar animators)

To Infinity and Beyond (my favorite of the Pixar books)

The Pixar Touch (a more business-oriented take on the company’s history)

Upcoming Pixar (a fairly comprehensive blog about Pixar developments)

Feel free to add to the list.

It takes me a little longer to write the kinds of posts I prefer to write, and sometimes my schedule gets complicated, so I can’t promise to have new posts available on a consistent schedule . That’s why I encourage you to sign up by email. You can do that by clicking here.

If you’re following along by email, you’ll know right away when I have a new post waiting for you. It is very easy to unsubscribe, and you won’t receive anything unrelated to my blog.

Lastly, if you appreciate my writing, why not write a comment or share the post with a friend? It would encourage me to keep sharing some of my heart with you.

As always, thanks for reading and God bless.