I believe in the American dream, the one that tells us that we can become anything we want to be with enough hard work and character. Dreams don’t always come true, but in America there is no king who orders our lives, no class structure that limits how far we can advance in society. Truly, our place in the world is not confined by our blood relations but by how useful we become to our fellow citizens.

Entrepreneurs embody that American dream. They take on enormous risk and devote time and money to offer goods or services that will, it is hoped, be valuable enough to sustain a business. In the process they provide jobs, revenue, and training to the community where they operate.

As long as we Americans remain free, we will continue to seek out all kinds of ways to better ourselves by improving the lives of others. Tragically, though, when profit at any cost becomes the only guiding principle of a business, it corrupts the very ideals that made the business possible.

For every irresponsible company like Enron, WorldCom, Massey, or BP, the pressure to regulate business grows, and if there is anything that a bureaucrat enjoys it’s fattening up the law books with more regulations.

Never forget, noble reader, that in some societies, sprawling government bureaucracies entirely dictate the ways their citizens live their lives. Watch The Lives of Others, if you want to see what that looks like.

Fortunately there’s a solution. It involves just 15 minutes a day doing some simple, relaxing exercises. Actually, those are the instructions for the AbMaster 3000, if I remember correctly. Sorry about that.

You know, you read one article about how great abs are an essential element of a vigorous foreign policy, and sometimes that’s all it takes to get your solutions mixed up. I mean that hypothetically, of course. I’m not the sort person who reads those articles or uses AbMasters, at least not on a daily basis.

Anyway, more regulations won’t prevent corrupt businesses from harming others. It’s the good guys, not the bad ones, who follow the rules, after all.

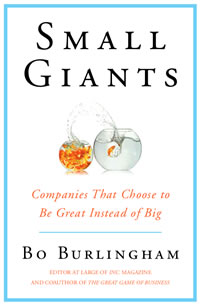

Whether you are involved in small or big business, whether you work for yourself or do volunteer work, I promise you’ll find something to appreciate in the book. If you don’t, then please let me know, and I will pay for your copy of the book. I’m serious about that.

In the book Mr. Burlingham profiles a few companies that have what he calls “mojo,” something special about the way they do things that has to be experienced to be understood.

What is it that gives a company mojo? As Geoffrey Rush’s characters likes to say in Shakespeare in Love, “I don’t know. It’s a mystery.” It’s one of those things that is hard to define in concrete terms, but Mr. B does give us some clues.

break

For one thing, the people at the business really believe in what they’re doing. It’s not just that phony reiterate-the-mission-statement-and-tap-dance-for-the-boss kind of thing. It’s real. It costs something to live up to ideals, and if the company ideals are there just to sound impressive then no one will sacrifice for them. When the business leaders are making the sacrifices for the things they value though, that’s when others start paying attention.

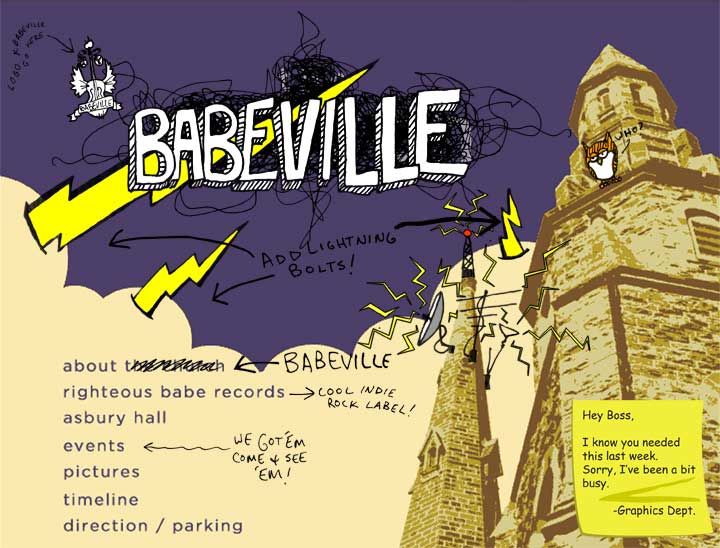

It’s contagious if you do it enough. One of the companies Mr. Burlingham profiles is Ani DeFranco’s music label: Righteous Babe. He tells of how they put together a folksy newsletter, meant to read like a personal conversation with Ani DeFranco herself. It’s free, but the label wants it to be so good that others would willingly pay for it.

That’s a lot of effort to pour into something that could be dismissed as just another platform for selling records, but the Righteous Babe people want to let the fans know that Ani is a different kind of musician.

Apparently word gets around. Mr. B reports that people travel from across the country to visit the studio and experience the difference.

Being surrounded by flashy beguilers, we’re conditioned to accept selling out as a notable way of life. (To be fair there are some decent-minded celebrities who bank on excellence. It’s just that bad apples are good at spoiling the barrel’s reputation, don’t you know.)

I get discouraged when companies and people I once admired compromise on quality or virtue in the name of more money, more power, more whatever. Don’t you? It adds some resistance to doing things the right way, and who really needs that?

I understand people make mistakes, and there’s always pressure to get results. I am far from a perfect person, so I’m not here to point fingers. I’m just asking you to stand for more than just supersizing yourself. (You know, you could do worse than looking to a God for that …) Zingerman’s Delicatessen takes pride in the quality of their sandwiches. They don’t ration out the meat in hopes of saving money.

They want to make a masterpiece that astonishes you. As a result people line up outside the store and endure long waits to experience the magic.

One company like that is enough to counterbalance 10 soulless ones. It stands as a beacon of hope, reminding us of what community-oriented greatness can be.BREAK

By now you may have noticed that I’ve used the word “community” a few times. That’s not an accident. It is a concept that keeps resurfacing in the book.

The Righteous Babe folks care about their Buffalo, NY community. They do everything possible to buy supplies from local vendors and hire people who live nearby. Sometimes that means having to pay more, but in doing so they can give back to the locals who support them.

Ober Tanner of O. C. Tanner Manufacturing, another profiled company in the book, is quoted as saying “I feel responsible for everyone here.” He is the kind of employer who says he wants his employees to receive happiness from their work and means it. The enthusiastic employees who treat him like a hero are the proof.

The Clif Bar company shows commitment to their community by paying their employees to do a few hours of volunteer work. The most intriguing part is that they let their employees pick the charities they’ll each get paid to help. Instead of streamlining the process, the Clif Bar executives want to give employees the freedom to support the causes they value.

As Mr. Burlingham explains, that sort of thing happens because Small Giants are companies whose first priority is serving the people inside of the company. The customers come second.

The idea is that you treat your people so well that they will fight for the things that matter to you. They’re not just coming in to get a paycheck. They’re doing their best for their family at work. It makes a difference.

Since we're talking about Clif Bar, now would be a good time to mention their site: clifbar.com. It's unique and conveys personality, and it's another reminder that the company stands for something. That's what good design can do.

Thanks to the Small Giants book, I’ve come to value the Clif Bar brand so much that I plan to buy their energy bars even if they cost more than the competition. Price isn’t everything.

There’s no way I could do justice to all the book’s ideas here. If you want to learn more, give the book a chance. It’s an easy read, even if you’re not normally into business books.

As a bonus, the writer practices what he preaches: Although it would probably be cheaper to print in China, the book is still printed in the USA. That’s not a fact Mr. Burlingham mentioned. I know it only because I checked.

“It’s not what we do. It’s who we are.” That’s the slogan for the Small Giants Community, a forum for entrepreneurs who want to live out the ideas in Mr. Burlingham’s book. Put differently, you don’t have to be part of a small business to be a Small Giant. You can work for a big business or you can go it alone.

It is mostly a matter of taking pride not in what you get from the world, but in the special things that only you can give. Do that while benefiting everyone involved and sustaining the endeavor, and you’ll really have something!

If you think that sounds a little idealistic, you’re right. But then, our country was founded on ideals, and there is something inherently American about being a Small Giant. When you’re blessed to live in a free society, you can take risks, dream, and dare to do things your own way, assuming that you follow the laws of the land. (Let us pray the laws do not devolve further into crippling monstrosities.)

Don’t listen to the politicians. America does not need more government control. We need more hardworking, character-driven Small Giants who are excited about sharing something special and profitable with their communities.

Let’s end with a quote from the author. “Having a great business is one way of making a better world.” Cheers to that.