If your life doesn’t have enough playtime then there might be something seriously wrong with you, at least that’s what Dr. Stuart Brown, founder of the National Institute of Play, suggests. I’ve been considering his ideas ever since a friend shared this video with me, and I think he might be on to something. The video is about thirty minutes long, but it’s worth watching. (You can see a larger version of the video on the TED site here.)

(This link was updated from the TED site to the YouTube one on April 11, 2012 due to embedding issues from TED’s site. The link is the same, but some links did not work properly when I migrated my blog from nsavides.wordpress.com to the current location.)

As a writer, I keep my eyes open for new ways to understand others (and myself). That’s not just about getting better at my craft, although that’s a nice bonus, but there is something intrinsically compelling and beautiful about getting closer and closer to the truth of a person.

After reflecting on Stuart Brown’s ideas, I’m now convinced that you can get a decent sense of a person just by considering his or her play history. At first that might seem silly, but let’s consider the idea a bit. Aren’t you a little more wary of someone with whom you’ve never shared a laugh? And if playtime was insignificant, why does our society value sports so highly?

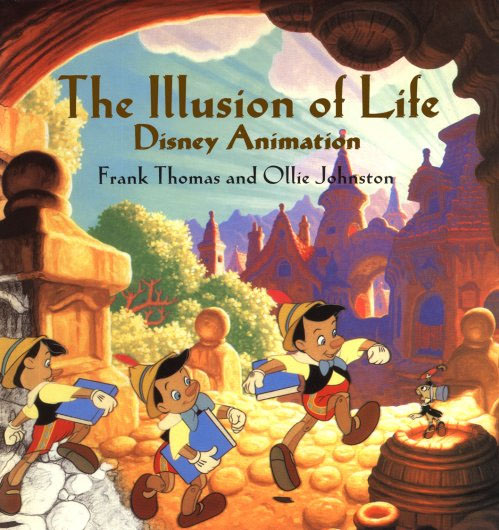

Professional athletes, highly skilled individuals who train extensively to play games in public, are some of the highest compensated members of our society. Successful movies, music and shows often feature visual gags, amusing variations on a theme, and witty dialogue (they don’t call them plays for nothing, folks). Let’s not forget about video games: According to the NPD Group, the United States video game industry generated more than $20 billion worth of revenue in 2008.

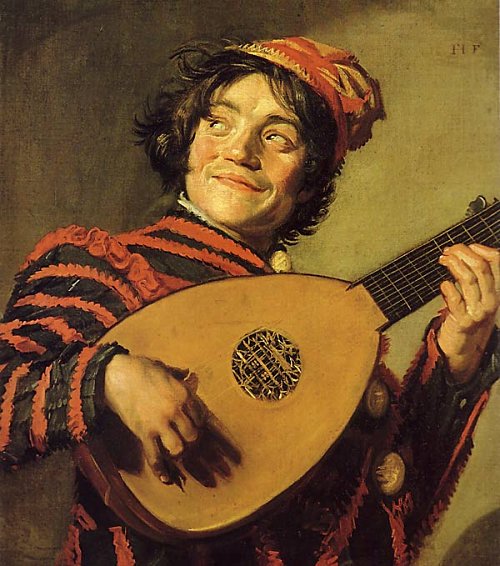

The Lute Player - Frans Hals

Playfulness isn’t just a financially valuable attribute to some folks. Frank Capra, the director of films like It’s a Wonderful Life, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, uses playfulness or its absence to reveal character. In Capra’s World War II documentary Why We Fight, the narrator asks us to, “take a good look at these humorless men.” This happens just as the camera reveals grim footage of men like Rudolf Hess, Hermann Goering, Joseph Goebbels, and Adolf Hitler.

The implication is that because these men appear humorless, they are not to be trusted. In comparison, consider what Capra says about comedy in his autobiography, The Name Above the Title: “Comedy is fulfillment, accomplishment, overcoming. It is victory over odds, a triumph of good over evil.” Did you get that? As far as Capra is concerned, comedy is what happens when goodness prevails, and without playfulness there is no comedy. It mixes well with the ideas of Dr. Brown, does it not?

Would you like a more contemporary example? No problem. In the world or Harry Potter, we are allowed to enjoy the playful side of magic only when we’re around the good kids. The bad guys are only interested in the magic that allows for cruelty and domination. Are you starting to see a pattern?

Perhaps this is a redundant point, but the moments that feel most corporate at work and in my personal life are decidedly unplayful ones. Work is going to be hard and frustrating sometimes, I know. Otherwise employers wouldn’t be so quick to entrust us with their hard-earned cash. That’s not what I’m getting at. I’m more interested in the cruel or banal moments in our lives that make it harder for us to keep alive our own inner sense of playfulness.

Being playful doesn’t have to be the polar opposite of doing business. That’s one of the key ideas from a different TED lecture given by a man who is also named Brown, Tim Brown in this case. He is also the CEO of the design firm IDEO as it happens. Here’s the video link, if you’re interested. (It’s the last video link in this post, I promise. Once again here’s the link to the video on TED.)

Tim Brown suggests that there is a connection between the playful environments of places like Google, Pixar, and IDEO and their ability to solve problems in creative, but also highly effective ways. It’s as if a playful environment makes it feel a little safer to bring a sense of a playfulness to the work at hand.

Research he references concludes that the most playful kids are the ones who come from the most stable and loving families. It follows, then, that companies who are smart enough to value playfulness should do whatever they can to make the workplace feel more like a supportive family.

Let’s get back to Stuart Brown, the guy from the first video. It’s interesting, isn’t it, that Stuart Brown doesn’t just ask us to set aside some time for playing. Instead, he advocates an ongoing state of playfulness. It’s a subtle distinction, but it’s worth addressing.

If play time becomes a mandated thing, then it could quickly turn into something ugly. By ugly I mean something like a mandatory Nerf-powered shootout in cubicle land where the ambivalent employees have to face off against the obnoxious office go-getters. Then playtime would get measured, and employees would get evaluated on key play metrics. At this point, the management folks would quite possibly turn this data into sheets of uncompelling bar-graphs, and these sheets would be distributed to unsuspecting employees in the name of promoting playfulness. Honestly though, whose idea of fun is that? (Not mine.)

Stuart Brown is right: The real magic happens when you can bring a sense of playfulness to any situation, but only a true saint can preserve a sense of inner playfulness even in the most trying of circumstances. Whenever I’ve seen the Dali Llama speak (on TV not in person), I’ve noticed an almost jovial lightness to him no matter what he is discussing. The Apostle Paul is another great example to consider. Even in jail he was writing about how he had learned, through the grace of God, to be content with all things.

I know being content and being playful don’t mean the same thing, although I do believe they go hand in hand. When was the last time you remember being simultaneously jealous and playful? What about being both playful and malicious or conniving?

I don’t about you, but my soul has been muddied from time to time with malicious or conniving inclinations. In those moments it wasn’t so hard to be persuasive or assertive. I could even muster up a kind of contrived imitation of playfulness, but I couldn’t be truly playful until I put aside, at least temporarily, those ignoble preoccupations. That’s why I buy into Stuart Brown’s claim that playfulness is an essential part of building trust.

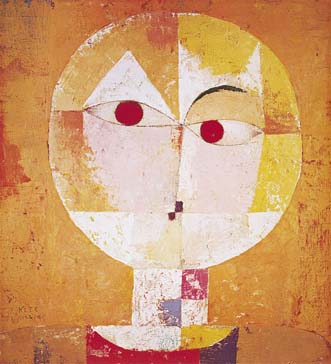

Senecio - Paul Klee

Now comes the warning: not everything done in the name of playfulness is good. Sometimes things are going to hurt. I think part of becoming an adult involves learning to face the pain in our lives without always looking for a way to anesthetize it, to make it seem more fun. It is the unfiltered sting of truth that lets us better see the broken parts of our lives, but many of us, myself included, find it easier to pour some sugar on our problems as we keep on dancing to the same old dissonant song.

Do you have friends who are always joking around even in serious moments? Those kinds of people might seem amusing enough right now, but what if ten years go by and they still aren’t working to improve the world around them? What about the hardcore gamer who stops providing for his family just so that he can play more games or the sports fan who does nothing but watch games on TV? What about the partygoers who bankrupt their futures just to buy a few more temporary thrills? These are all examples of how an inclination toward playfulness can turn tragic.

Stuart Brown tells his patients to explore the most joyous moments of their lives and to adjust their lives accordingly. That’s great advice. Let me also suggest that it might be helpful to consider the moments in your life when being playful seems most difficult or when your inclination to play seems most excessive. Do what you can to figure out what it was that robbed you of your ability to enjoy the moment in those situations, and then try to face similar situations in a better way.

I’m going to explain that in a kind of indirect way but also in a personal way, so bear with me. It’s not easy for me to use myself as an example: writing honestly and in a personal manner doesn’t always make me look good, but I wouldn’t respect myself as a writer if I did any less. In my more optimistic moments I believe that by being honest about my struggles, I can help both you and me in the process. The wisdom or foolishness of that concept will, I’m sure, reveal itself over time.

In any case, with my life being what it is, I have to believe that the truth, and not my profit margins or my badass quotient, can eventually set me free, free to be the best version of myself, the man I someday hope to be. Maybe you think that’s a foolish thing to believe. Maybe you’d rather get tips on expanding market share or becoming more of a badass? If so, then by all means go and find something else to read.

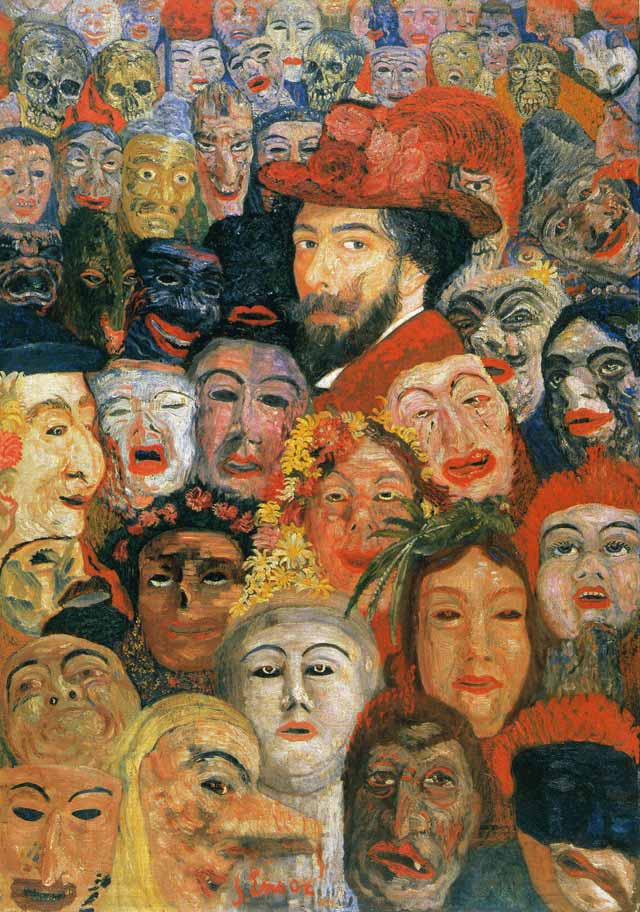

Intrigue - James Ensor

But then, maybe a few of you can relate? If so, then thanks for sticking around. I hope I can reward you for your patience and your desire to get beyond the surface of things.

With that said, here are some examples of when it is hard for me to be playful. In the past, I had difficulty finding a sense of playfulness about my work. It was too important to joke about because it was the only way I knew of determining my value as a person. It was an awful way to live.

Now I’d like to think that I don’t take my work as seriously. I’m participating in a silly one-act play over at the Smithfield Little Theater later today, for example, but sometimes I still get caught up in the belief that my work is the only thing that matters in my life. Kind of a corporate way to think, right? I know, but when I think that way, I don’t have to put myself in a vulnerable position when dealing with others.

Speaking of other people, I have a hard time remembering playful moments that I shared with my dad when he was still alive. My mom and my sisters played lots of games with me, but not my dad. Like many other dads, he was too busy with work and with other pursuits to have much time to play with me.

He was helping his patients fight off cancer, and that is admirable enough, and yet the absence of a dependable and playful father figure in my childhood made it harder for me to bond with other guys, whether in sports or in class. It is still hard for me to form lasting, sincere and playful friendships with others. Don’t get me wrong: ultimately, I hold myself responsible for the quality of my relationships, but my dad’s interactions with me didn’t make this kind of thing easier.

Earlier I mentioned an admiration for the Apostle Paul’s ability to be content regardless of his situation. I am, on certain days, the exact opposite of the Apostle Paul: I sometimes have difficulty finding a sense of harmony, of playfulness, even in the most comfortable of settings, and in those moments my world becomes unbearable.

Self Portrait with Masks - James Ensor

Anything that can make the moment feel more enjoyable becomes very appealing, whether or not it is good for my long-term goals or even my soul. In those God-forsaken, loveless moments, the only thing that matters to me is finding some way back to that illusive state of bliss, no matter what it takes. I try to avoid taking the easy way out when tempted by such toxic siren songs, but I don’t always succeed.

Yes, sometimes I’m the guy who is pursuing playfulness in the wrong way, the one who laughs too much, the one who has a few too many drinks. I’ve been the guy at the party who has made others shake their heads with disapproval and ponder the uncivilized creatures that this world can produce. It does wound me so to get that reaction, and yet that’s probably the look I would give to myself if I was a third-party observer.

I try very hard not to be that guy, but sometimes it is easier to laugh and joke and make an ass of myself than to face the truth of the moment. The only remedy I know for that kind of thing is to acknowledge the pain, to give the moment back to God, and to open my heart to the love that’s out there. It’s not an easy remedy, and I’m not good at adhering to it, but it’s the only thing that seems to work even in a subtle way.

In the book City of God, Saint Augustine writes about the importance of enjoying the presence of God. He writes that no one is foolish enough to suggest that a man who drinks from a fountain is doing something good for the fountain. Nor does a lamp benefit when a traveller uses it to navigate. Why then, asks Augustine, do people assume that God is meant to be loved and enjoyed for the sake of God and not for the good of the souls who love and enjoy Him?

I believe the only way anyone can maintain the ongoing sense of playfulness that Stuart Brown advocates is to enjoy the presence of God moment by moment. It’s OK if your conception of God is different than mine. You might not even believe in God, and you might be better off in this life than I am. Obviously, I don’t have it all figured out, so there’s no reason why you should take my advice if it doesn’t somehow ring true.

Even so, I still think you might benefit by trying to reconcile yourself moment by moment with something bigger than you, a higher power if you will, in case you find that phrase less objectionable than the word, “God.” If you and I diligently seek out the truth,uncomfortable though it may be, and listen carefully to the still small voice that speaks with love inside our hearts, then I believe (when I am not distracted by anger or despair) that someday we’ll wake up and discover that our worlds are once again filled with playful possibility. Why take my word for it, though? My soul is, after all, still a murky blend of light and darkness. Seek for yourself.

Several Circles - Wassily Kandinsky

(This is one of my favorite abstract paintings. It made an impression from the moment I saw it. Serene and playful, the circles gracefully overpower the darkness around them.)

Let me end with another reference to Frank Capra. Towards the end of his life, Capra was involved in a video tribute for the late director George Stevens, the man responsible for Shane and other cinema classics. I was captivated by Capra’s playful demeanor even in old age. Up to that point, I had assumed that older people were by definition more severe than younger folks. Frank Capra, though, had more vitality and twinkle than a lot of kids I know.

He was talking about looking up George Stevens when he got to heaven so that they could work on something special together. That kind of cheerful disregard towards death is what it can look like when the good kind of playfulness prevails. And so, I’m going to pray for more of that kind of playfulness for me and for you. Here’s to a more playful, less corporate world!

It takes me a little longer to write the kinds of posts I prefer to write, and sometimes my schedule gets complicated, so I can’t promise to have new posts available on a consistent schedule . That’s why I encourage you to sign up by email. You can do that by clicking here.

If you’re following along by email, you’ll know right away when I have a new post waiting for you. It is very easy to unsubscribe, and you won’t receive anything unrelated to my blog.

Lastly, if you appreciate my writing, why not write a comment or share the post with a friend? It would encourage me to keep sharing some of my heart with you.