In this post, I will strive to convince you that M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water, a film that got nominated for a Razzie, is in fact a masterpiece worthy of esteem. As you may know, Razzies are awards that acknowledge (or shame) the worst film achievements of the year.

Some of the winners of this coveted prize include cinematic gems like Battlefield Earth, Freddy Got Fingered, and Gigli. But, let’s be fair here; Lady in the Water didn’t win the award. It merely got nominated. Still, I have my work cut out for me. That’s all right. I enjoy a challenge.

Stars – Maxfield Parrish, 1926

break

Since this movie has gotten such a negative reception, I’m going to discuss it in more depth than usual. I understand this might not be of interest to everyone, so feel free to jump around, either on the page or, you know, literally jump around while reading this. If nothing else you’ll get a good workout.

Alternatively, you could just go and watch the new Kanye West video and then pretend afterwards that you actually read my thoughts. Still, maybe you’ll find something of interest if you’re patient enough. In case what I have to say matters to you though, please do what you can to read all the way through before reacting. I mean well, but sometimes things get lost in translation. Pray with me that something positive comes through. With that said, onward we go!

I’ll admit it: Lady in the Water is no Citizen Kane. Citizen Kane is, after all, lavishly praised by cineastes across the globe. Even as you’re reading this, there’s quite likely a spectacled professor in northern Latvia who is explaining to his sleepy students that the film is one of the finest ever made. I’m fairly certain that no film intellectual is speaking of Lady in the Water in similar terms.

I say fairly certain because the fine film critics in the Polynesian island of Tuvalu failed to complete my survey on the matter. Come to think of it, no one returned my survey. Next time, I’m going to put a little more thought in the stationary I use for such things. I’ve learned the hard way that not everyone shares my passion for embroidered dragons. Alas.

Seriously though, critical acclaim or the lack there of shouldn’t be the sole determining factor of a film’s merit. Sometimes the critics get it wrong. I wish I could claim that the story I’m about to tell you is another element of my imagination, but this one’s true:

When I was in college, a philosophical group on campus was hosting a get-to-know-you social. The event involved coming to the library to eat cookies and to watch a supposedly important film. (It doesn’t get much better than that, right?)

I don’t remember the name of the film, but it featured the main character in an extensive rape sequence. It wasn’t a sequence that was designed to show the horror or tragedy of rape. On the contrary, it emphasized the will to power of the “hero.” The creepy intellectual in charge of the event acknowledged as much in the discussion afterwards. Some icebreaker huh?

Hansel and Gretel illustration – Gustaf Tenggren, 1942

break

Believing that the “experts” knew something I didn’t, I stuck it out to the end trying to understand what I was missing. I placed more value on the judgement of others than on my own intuitive sense about things, and so I got led astray. Now I know better.

I never returned to that group, but I might have actually gotten to know the people in it had they shown a film like Lady in the Water. I’m no scientist, but I have this hypothesis that movies with warmth and heart tend to get people to open up more so than intellectualized rape films. Maybe that’s just me, though.

Prior to making Lady in the Water, Mr. Shyamalan had made smart thrillers with a twist at the end. Lady in the Water was a bit of a departure from that. In the special features for the disc, Mr. Shyamalan talks about how the story originated as a fairy tale that he would tell his kids. He also mentions being inspired by how Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel had a positive impact on the world.

(The book he’s referencing is Uncle Tom’s Cabin, one that many historians credit for helping to end slavery in America. It is worth reading not merely for its historical significance but also for its compelling story that showcases the Christian ethic prevailing against cruelty.)

Listening to Mr. Shyamalan talk about the movie, I get the sense that he cherishes it very much and wants to see it find a receptive home in the hearts of his audience.

Goblin Market illustration – Arthur Rackham, 1933

break

Well that’s all well and good, but we all know what they say about good intentions. The road to hell is supposedly paved with them. As a side note, how is it that the people who say such things actually know what the road to hell is like? Have they actually been there, or were they just part the construction crew that helped to smooth the path? Times are tough, so people take whatever jobs they can, I guess. But anyway, does the film actually deliver?

I think it does. On the surface level the movie is about a nymph in the pool of an apartment complex who is trying to return to her people. Spend some time with the movie though, and you’ll discover a beautiful story about the source of inspiration, about finding one’s purpose in the world.

Paul Giamatti plays Cleveland Heap, a man who has lost a sense of connection to the world after facing tragedy. He trudges through his days doing mundane work until he meets a Narf, a nymph-like creature. The Narf he meets is called Story, played by the captivating Bryce Dallas Howard who returns to work with Mr. Shyamalan after collaborating with him on The Village.

We learn that Story, like other Narfs before her, leaves the blue world below and risks grave danger so that she may be seen by the vessel, someone who needs her inspiration to do important work.

It is no accident that the Narf is named Story, since this is a fairytale about the power of stories. Stories come into our lives for just a moment, but the special ones change our lives in ways that we can’t quite articulate, Mr. Shyamalan suggests with that naming choice.

The Frog Prince illustration – Warwick Goble

break

When we meet most of the characters, we see them living muddled lives. Either they’ve isolated themselves from others, or they’re doing unusual things in the hope of becoming unique enough to validate their existence. Story comes into this world and only then do the characters find their purpose and come together in community.

In the beginning of the movie, characters have conversations with each other, but the camera only shows us one face. The other person is seen from behind or kept out of focus. Establishing shots or reaction shots are conspicuously absent.

By going against the conventions we’ve come to expect in film, Mr. Shyamalan makes us sense that something is not quite right, that we are somehow not connecting with the characters. This is an appropriate way to introduce us to Cleveland’s world, since it reflects the way he feels. Contrast this with the more accessible group shots at the end of the movie, and you’ll get some sense of the journey that the movie offers.

When Story the Narf appears we see more establishing and reaction shots. As Story’s influence grows so too does the number of people in the frame and the color saturation. The colors are no longer muffled and flat but vibrant and soothing.

Alice in Wonderland illustration – John Tenniel, 1865

break

Also worth mentioning is the significant number of shots that involve something out of focus in the foreground. Slowly the focus brings clarity, something the characters also discover by the end of the movie.

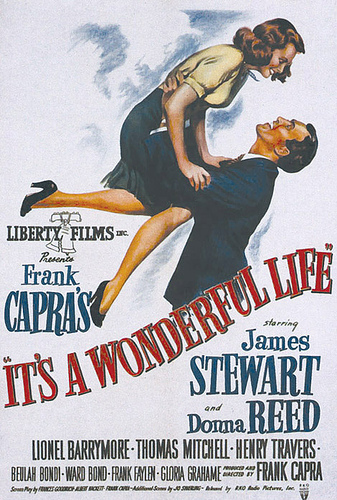

The idea that Story bring clarity is reenforced by Cleveland’s way of speaking. He stutters until he meets her, and then his stutter goes away. It’s sort of like what happens to George Bailey when he gets a visit from Clarence the angel in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. (More of my thoughts on Capra are here.) It’s as if there is something divine about Story that improves all who approach her with receptive hearts.

As far as I know every ancient society had some kind of belief in divine inspiration. Hence the invocation of the muse. Now days in our industrialized world we’ve moved away from that kind of thinking, but as writer Elizabeth Gilbert suggests in this TED video, maybe that is not for the best. We have turned away from the mysterious and pursued rigid structures and scientific methods; Sure, we have more technology, but also more violence and alienation.

What if it wasn’t meant to be that way, asks Lady in the Water? What if we all have a bigger purpose? What if we need each other and a rediscovered sense of child-like innocence to discover that purpose?

The Lady Gave her Purse – Warwick Goble

break

Child-like innocence is an important part of any fairy tale, but in this movie Mr. Shyamalan calls our attention to it.

In order to learn more about Story, Cleveland approaches an Asian lady who has heard folktales about the Narfs. To hear more of the story behind Story, Cleveland must act like a child to gain the woman’s trust. Later, Cleveland and his recruits discover that their Interpreter, the one who can interpret all the signs in the story that they’ve experiencing, is actually the youngest boy in the group. It’s a little Postmodern, but so is everything these days.

Perhaps a few critics were not kind to Lady in the Water due to its depiction of a film critic, played by Bob Balaban. It’s definitely not a flattering depiction: He’s smug and self-absorbed, he gets everything wrong, and meets a tragic demise. Well, here’s the thing: many critics are smug and self absorbed. Too often it feels like they obsess about the wrapping paper of a film (or a book or any work of art really) and fail to open it up and acknowledge the gift inside.

The Tortoise and the Hare illustration – Arthur Rackham, 1912

break

I do appreciate the thoughtful commentary that some critics bring to the table, but I’m less grateful for the one who go on and on about the genius of an arthouse rape film while heaping contempt upon the movies that bring joy and hope to others. I truly believe that those kinds of critics are warped and frustrated creatures who seek, consciously or unconsciously, to spread their crookedness into others.

With that said, I don’t think Mr. Shyamalan was trying to critic proof his film. I think he was trying to protect himself a bit from the critical beating he anticipated. You see, he gave himself an important, but a very vulnerable, part in his movie.

He plays Vic Ran, the writer that Story has come to inspire. When we first see Vic, his sister explains that he will do anything, even laundry, to avoid writing. He’s working on something called the Cookbook, a title that Vic acknowledges is kind of dumb. A glamorous character this is not.

Again, note the name. Vic Ran is someone more inclined to run away than do something creative. That’s actually a very humble role for Mr. Shyamalan to give himself, considering that he is responsible for writing, producing, and directing films that have grossed millions of dollars. (Lady in the Water hater, when was the last time you produced something that others valued throughout the world?)

Considering his status in Hollywood, Mr. Shyamalan could have given himself the part of a mighty king who gets all the girls and has ferocious, computer-enhanced abs of steel. Instead, he chose to play an ordinary guy who becomes inspired to create something extraordinary. Here’s what Mr. Shyamalan said about the part, “I play Vic who is genuinely an ordinary guy, which is what I feel every single day, but he is someone who is also capable of doing beautiful things, as everyone is capable of doing beautiful things.”

Alice in Wonderland illustration – John Tenniel, 1865

break

Still, the critics wailed. “Look at him, playing a writer who is meant to write something important! The vanity! The hubris! Who does he think he is? Does his work appear in Pretentious Monthly? Mine does. I write important things about collectivism, and imperialism, and all kinds of isms, and he writes drivel, sheer escapist nonsense for the dirty masses.” No, I didn’t find critics to go on record with those words, but that’s my best guess at their inner monologues based on their rather predicable comments about the film.

(OK, that’s a somewhat exaggerated inner monologue. It’s what I like to call a heroic attempt at humor, so bear with me as I pause for the laughter to subside. And … pause for the laughter to subside. I know, I know. Don’t quit the day job, right? Hmm … such unique tips you offer, my friends.)

To be fair, many critics did response favorably to Mr. Shyamalan’s earlier, more conventional thrillers. To them, I’m guessing Lady in the Water was a little too different, a little too self aware, and maybe, just maybe, it hit a little too close to home.

Mr. Shyamalan is a pretty sharp guy, so I’m sure he had some sense of what the critics would say. After all, it’s not all that hard to anticipate the reactions of the smug and the self important. Maybe that’s why he foreshadowed the death of his character. “Is someone going to kill me because I write this?” he asks Story. She confirms.

Lady in the Water is not the first film to suggest that the artist might have to die for his art. In The Red Shoes, the cinematic masterpiece from British directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the performers sacrifice their love and their lives to serve a sinister theater impresario, a monstrous man who values artistic achievement above all else. In Lady in the Water, the aspiring artist approaches his work with an open heart and prepares to sacrifice himself so that others might benefit. With which kind of artist would you prefer to collaborate?

I can only guess at how anguishing it must have been for Mr. Shyamalan to see a story close to his heart, one that grew out of a bedtime story for his kids, get such a brutal reception. From my own experience and from listening to other creative people, I do know that rejection hurts more when the work is personal.

Little Red Riding Hood illustration – Gustaf Tenggren

break

The movie Mr. Shyamalan made after Lady in the Water was the Happening, which is in my opinion the worst of his films. It felt like he lost his way. My guess is that the pain of Lady in the Water‘s reception made it harder for him to trust his instincts. Instead he tried to tap into the environmental zeitgeist and make something that he thought others would want. As far as I know, Mr. Shyamalan hasn’t gone on record about the Lady in the Water‘s unfavorable reception, so that’s just a guess.

Even so, I’m willing to bet that Mr. Shyamalan anticipated the heartache that would come from making the movie. Yet, he chose to make it anyway, believing that some good might come out of it. He wouldn’t have mentioned Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book if he didn’t believe that. That’s heroic, ladies and gentlemen. I’m grateful for that.

There’s a sense of harmony in the film that comforts me whenever I watch it. It’s the movie I watch when I feel disconnected from the world or when I feel like my own creative endeavors don’t matter.

East of the Sun and West of the Moon illustration – Kay Nielsen, 1914

break

The way Mr. Shyamalan put himself into his work in such a vulnerable way has stuck with me even more than the themes of the story. His openness encouraged me and made me want to do the same for others, even when it is uncomfortable for me to do.

I’ve definitely lost several hours of sleep in regards to some of the things I’ve written, but I take comfort from others who strive for a similar strand of difficult honesty, and so I try to pay it forward. It’s my way of battling the suffocating, my-product-is-awesome! commentary that floods the web.

Is selling widgets or selling yourself so important that you are willing to demoralize others in the process? Some critics would say yes. Mr. Shyamalan wouldn’t, at least I’d like to think so.

Since we’re being honest, I will admit that I almost didn’t finish writing this post. Movies like Lady in the Water have prodded me to search for purpose in my own life, and that search can sting when you don’t get the answers quite right. Mr. Shayamalan acknowledges as much in the movie. When Cleveland gets purpose wrong, it causes suffering and almost leads to the death of someone he’s come to cherish.

Ballet – Kay Nielsen

break

I can relate. Recently, I had come to believe that there was something I was supposed to do in relation to the victories of the New York Giants. I won’t explain it here, because it will take a while, and it will sound crazy.

If you follow me on Twitter, you might have more of an idea of what I’m talking about. (If you go all the way back to the beginning of my updates and check the dates, then maybe you will conclude that I’m not as crazy as you first thought. Doing that is more than I could stomach though, so I won’t recommend it for most of you.)

Anyway, there were enough moments that happened just so to convince me that I was going in the right direction. Then, the Giants lost and to the Cowboys of all teams.

I felt so foolish and so wrong about everything. My initial reaction was to numb that irksome inner voice into oblivion so that I would never again hear it to prod me toward a supposed higher purpose. Either I was wrong about something that seemed so right at the time, or I did something along the way to change the outcome.

Neither possibility is very comforting. There is also the possibility that I was meant to do something that would fail and cause me more anguish. That is the least comfortable possibility of the three.

It might have all been wishful thinking, and yet why did all the circumstances come together as they did? What about my moments of defiance where I sensed that making certain choices might jeopardize the outcome I wanted, and yet I went ahead with those choices?

The ironic thing is that my moments of defiance were my ways of dealing with the stress of doing something that felt, at the time, like something daunting that I was meant to do. Why then would I be asked to do something beyond my capacities to handle gracefully?

Enchanted Prince – Maxfield Parrish

break

If I’m never able to answer these questions with some sense of satisfaction, then I probably won’t trust my instincts to the same extent as before. Still, if I really believed that searching for purpose is an entirely stupid endeavor, then I wouldn’t be able to publish a favorable piece about Lady in the Water, a movie that so strongly embraces the search for purpose.

I started writing this a week before the Giants lost, but I didn’t have time to finish it until now. I don’t think I would have taken on the subject had I waited until this week to start it.

In spite of the additional lack of sleep that this post will probably bring me, I’m going to finish it because I still believe that things happen for a reason and that trying to make sense of purpose is a worthwhile pursuit. The risk of getting things wrong isn’t unsubstantial, but the sense of fulfillment and harmony that can come from getting things right is worth the cost.

It hurts to say, but I’m still grateful to Lady in the Water for encouraging me to look for purpose. Give the movie a chance, and maybe you too will be grateful for its existence.

In this season of Thanksgiving, let us of course remember the men and women who choose to risk their lives in combat so that we can live in freedom and security. Theirs is often the ultimate sacrifice. But, let us also remember the entrepreneurs, the artists, and the dreamers, the people like M. Night Shyamalan who risk their careers, their creativity capacities, and their well being in the hopes of producing something special for us.

Good Luck Befriend Thee – Warwick Goble

break

Lady in the Water is no Citizen Kane, but that’s a good thing. A work of art should stand on its own, offering a unique gift to the world. Whatever the movie may be, I still cherish it. Thank you for making it, M. Night Shyamalan.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone and God bless.

break

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post or some of the others I’ve written, consider signing up to get my posts by email. You can do that by clicking here. I don’t write every week. If I did, I wouldn’t have the time to write the kinds of posts I prefer to write.

I only write if I believe I have something worth writing and after I’ve spent some time finessing my thoughts. If you’re following along by email, you’ll know right away when I have a new post waiting for you, whether that’s next week or a month from now. It is very easy to unsubscribe, and you won’t receive anything unrelated to my blog. As always, thank you for reading.