It’s not just that Frank Capra is a great director or that his movies are a big part of why I want to make movies. Both points are true, but it goes beyond that. Ever since I saw his films as kid, there was a part of me that wanted to somehow find my way into the Capra world. I didn’t realize this until a few months ago, at least not consciously. Until then that wish was hiding somewhere in the back of my mind, subtly influencing my choices throughout the years.

Time Magazine cover: Aug. 8, 1938. (Cinema: Columbia’s Gem, written as You Can’t Take It With You was coming to theaters.)

To those of you who are already starting to fidget in your seats, I see you! Well, I don’t, but I’m imagining that I can, and it looks like you might spill your coffee if you keep it up, you impatient cinema enthusiasts, you.

Not to worry, I am going to talk about Frank Capra’s movies. I went back and watched as many of them as I could find, including the documentaries. I read his interviews and his autobiography. I even read his critics. But, I’m also going to talk about how his movies affected me.

Art is meant to have an impact on its audience, after all, so why try to sterilize the subjective experience out of the discussion? If you prefer straight analysis, I suppose you could read Cahiers du Cinéma or something equally pretentious, I mean prestigious.

Poster for It Happened One Night, 1934

break

With that said, what are some of the qualities that make Capra’s films so special? There’s playfulness for starters. Mr. Capra began his career writing gags for the silent-era comedians, and he’s carried that comedic training into the films he directed. Some comedy-oriented performers and directors dismiss the value of what they do. Not Frank Capra.

“Comedy is fulfillment, accomplishment, overcoming. It is victory over odds, a triumph of good over evil,” he explains. He saw great merit in making people laugh, and so he worked diligently at his craft. Maybe that’s why his screwball comedy It Happened One Night was the first film ever to win an Academy Award for both Best Picture and Best Director.

Photo credit: flickr.com/uw_digital_images, 1909

break

In the Why We Fight series of documentaries that Capra directed during World War II, prominent Nazis and Japanese adversaries are described as being “humorless men.” Them’s fighting words, at least to Capra; To be humorless is to be villainous in Capra’s movies.

Consider: Mean ole Mr. Potter in It’s A Wonderful Life doesn’t bother with jokes. He’s too busy with financial concerns.

In Hole in the Head, Frank Sinatra plays a fun-loving gambler who struggles to take care of his son. He makes mistakes, but we’re meant to root for him. Sinatra’s more responsible, but sullen brother, played by Edward G. Robinson, is the antagonist. About his reckless brother whom he has spent most of the movie condemning, Robinsson finally concludes, “he’s broke, but he’s not poor. We’re poor.” The ending leaves some hope that even the uptight brother will learn to love and play.

Indeed, rediscovering playfulness is essential for any Capra heel who wants to turn good. In Riding High, the dad is the humorless business tycoon who stands in the way of the young lovers getting married, but he eventually grows tired of being the stuffed shirt. With previously unseen jubilation, he tells his guests that he’ll be running away with the young couple. Then he dances triumphantly to their car.

An even better example is found in You Can’t Take it With You. This time Edward Arnold plays the baddie who happens to be—wait for it ladies and gentlemen—another heartless, money-minded man. He puts the squeeze on a hard-working family, but in the process he gets to know the father of the house.

Arnold eventually reveals that he used to once play the harmonica, Capra’s way of telling us that he wasn’t always such a bad guy. When he’s moved by the strength of character that he sees in the family, Arnold renounces his selfish ways. That happens shortly after he receives a harmonica as a gift. By the end, Arnold is all smiles, playing music with the rest of the family.

Photo credit: flickr.com/uaarchives, 1917

break

To prepare for this post, I even forced myself to watch Frank Capra’s made-for-TV science documentaries. I remember the awfully boring science videos I was shown in school, and I was not keen on re-experiencing them. I looked for something potentially more exciting to do … like flossing. If I skipped the videos I could do quite a bit of flossing, after all, and that way, for the first time in my life, I could go to the dentist without being embarrassed when the flossing questions come up.

“Tell me, Mr. Savides, when was the last time you flossed?” “Just yesterday.” “I see. And how long did you floss?” “Two and a half hours.” That would shut him up, don’t you think? It could have been a glorious triumph for me, but it was not meant to be. I watched the Capra documentaries, and consequently I am still embarrassed by flossing questions.

My flossing sacrifice was not in vain, however. While my dentist might disagree, I think I made the right choice. The science videos were not just informative but personable, imaginative and even amusing. The one I enjoyed most was “The Strange Case of the Cosmic Rays.” It features puppet versions of Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens, and my favorite, the intoxicated Dostoevsky presiding over a mystery-writing contest.

Debonair scientists make a case that their scientific inquiries about cosmic rays should be up for consideration. They show cartoon sequences to explain their research, while my boy Dostoevsky pours himself more vodka and struggles to stay awake. I learned more science from those videos than from several humorless, strictly academic lectures that I’ve endured throughout the years.

Photo credit: flickr.com/library_of_congress

break

Another aspect of Frank Capra’s work that I admire is his love of America. He was born in Sicily, and he came to America as an immigrant. His family was poor, and I imagine even discriminated against, but Capra never lost sight of how good we have it here. His affection for America is sometimes revealed by a subtle reference to a national pastime like baseball. In some of his best work, though, (films like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Meet John Doe, Why We Fight, and It’s a Wonderful Life come to mind) defending what’s right about America is a central preoccupation.

I still get chills whenever I hear some of the speeches from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Here’s one of them: “Just get up off the ground, that’s all I ask. Get up there with that lady that stands for liberty, take a look at this country through her eyes if you really want to see something, and you won’t just see scenery—you’ll see the whole parade of what man’s carved out for himself after centuries of fighting and fighting for something better than just jungle law, fighting so’s he can stand on his own two feet—free and decent, like he was created—no matter what his race, color or creed. That’s what you’ll see. There’s no place out there for graft or greed or lies or compromise with human liberties. And if that’s what the grown-ups have done to this world that was given to them we’d better get those boy’s camps started fast and see what the kids can do, and it is not too late because this country is bigger than the Taylors, or you or me, or anything else. Great principles don’t get lost once they come to light. They’re right here. You just have to see them.”

Photo credit: flickr.com/cornelluniversitylibrary, 1888

Some of Capra’s critics accuse him of creating a sugar-coated view of the country. They sneeringly describe it as Capracorn, but their critiques are unfair. Capra shows the bad along with the good. In State of the Union, one politician in power spots one of the good guys and asks his friend, “”How did he get in here? He’s honest.” Sure, Mr Smith Goes to Washington showcases idealism, but that idealism is put through the fire and mocked by the film’s gaggle of world-weary cynics. It prevails only after battling to survive.

In fact, that film was met with outrage and protest when it was first screened in DC. The politicians and press representatives were displeased that it portrayed their professions as being susceptible to corruption. Capra didn’t turn a blind-eye to America’s flaws, but he still believed in and celebrated its potential. As proof of that, he named his production company Liberty Films, and used the Liberty Bell as the logo.

I wish more of today’s hipsters would show gratitude for the freedoms their country provides, even as they address some of the problems they see in America. Unfortunately, these days it’s basically uncool to talk about love of country, especially if you’re an aspiring creative type. Be that as it may, Frank Capra offers a reassuring example that you can be both an engaged patriot and a successful artist.

What’s more, Capra didn’t support his country with just empty words. At the height of his success as a director, right when the US began fighting in World War II, he contacted the Army to help with the war effort.

He committed to making several films to show his countrymen why they had to fight the German and Japanese oppressors. That meant giving up a significant amount of time that could have been spent doing more profitable or prestigious projects. When was the last time you heard of a contemporary celebrity doing something like that?

Photo credit: flickr.com/library_of_congress, ca. 1905-1910

break

If my imagination is right, then you’re starting to look a little too serious, diligent blog reader. Well, I guess it is serious stuff, and you’ve been reading for a while without encountering any more attempts at humor. (Depending on your perspective, that might be a blessing.)

However you may feel about the matter, I want to do something about it. That’s why I hired a few mimes to help me with the jokes. But you know, it’s not working out so well; they’re not saying anything. Maybe next time.

In my defense, I guess I could mention that my dog ate my jokes, at least the funny ones. I don’t have a dog, but if I did, I’m sure he would have eaten pages of jokes by now. Assuming that these jokes in question involved some thought, which is admittedly a big assumption, then the theoretical dog would be in the unusual position of having thought for food. I’m not sure what that means, but presumably there are philosophers out there trying to find out. For now, let’s just keep on marching.

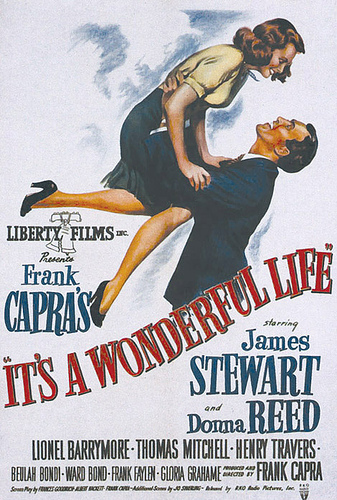

Poster for It’s A Wonderful Life, 1946

break

Think back to the scene in It’s a Wonderful Life where a desperate George Bailey goes to Potter to borrow some money. Uncle Billy had misplaced $8,000 dollars, but when Potter interrogates, George takes full responsibility for the mistake. I recall thinking something like, “Oh, so that’s what it looks like when a good man is facing a crisis.”I don’t often get to see intimate displays of integrity in the real world, so I’m captivated whenever Capra gives me the opportunity to do so in his films.

Essentially, a Capra hero is a man of character who faces the temptation of giving up his ideals, of selling out in the name of convenience. George takes a cigar from Potter before deciding not to yield. In Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Jefferson Smith’s mentor Senator Paine pleads with him to compromise for the sake of advancing his career. When Longfellow Deeds is betrayed by the city gal he tried to help in Mr. Deeds Comes to Town, he questions his small-town values and considers giving in to the vultures who want his money.

Promotional material for The Strong Man, 1926

break

The absence of just one man of principle is enough to turn a charming Capra town into a vice-ridden slum. That’s what Bedford Falls would be without George Bailey. We see hints of that even in Capra’s silent film The Strong Man, which stars the wonderful, vastly underrated Harry Langdon. In that film, the town hall becomes a decadent vaudevillian house when the local authorities accept bribes. A title card explains: “Justice and decency had fled before the new law — money.” Only the minister refuses to sell out; he leads the town in opposing the gangsters. Eventually order is restored and the town hall becomes a place of justice once again.

It’s not an accident that the minister is the restorative force. There is an undercurrent of faith throughout Capra’s work. Jefferson Smith is encouraged to look to a higher power when he despairs. In both It’s a Wonderful Life and Meet John Doe, the hero is rescued from tragedy on Christmas day. As if that weren’t symbolic enough, the dialogue in Meet John Doe goes so far as to associate the hero with Christ.

Photo credit: flickr.com/library_of_congress, 1942

break

The Why We Fight documentaries set up two opposing worlds, the free world vs. the slave world, similar to how St. Augustine sets up two opposing cities in his theological masterpiece City of God. In the free world, leisure-minded men and women care about each other, order their own lives, and worship God as they please. In comparison, the slave world deprives its citizens of choice and aims to “take children from the faith of their fathers and teach them that the state is the only church and the head of the state is the voice of God.” (What is a modern-day example of a political leader who gets the messianic treatment from his followers, whose image is plastered everywhere as if it were a religious icon? It does sound familiar…)

In his autobiography, The Name Above the Title, Frank Capra talks about how being director means that he has the opportunity to talk to millions of people in the dark for hours at a time. Dictators kill for that kind of access, and so he feels a strong responsibility to make it count for good. “My films must let every man, woman, and child know that God loves them, and that I love them, and that peace and salvation will become a reality only when they learn to love each,” he writes. Wow, thanks for that Mr. Capra.

Photo credit: flickr.com/kevharb

break

Maybe that’s why I’ve never been demoralized by watching a single Capra film. I can’t say the same about many of today’s contemporary artists, but they probably don’t share Capra’s esteem and affection for his audience.

To be fair, this is an issue I struggle with as well. Looking back, I’ve acted in one or two shows where my character had more swearing than I’d prefer. I didn’t think about it at the time, reasoning that the story had some merit and that I needed to get experience, but maybe I influenced some of the audience to be less civil with their speech. This is not to say that artists should avoid any questionable material, but there is something to be said about considering how your work will affect others.

The tricky thing with drama is that it deals with vice and human frailty. If you don’t show it at all, then you aren’t telling the truth. But if you show it in such a way as to glamorize it, then you risk corrupting the audience. Somehow Capra found a way to deal with corruption, violence, sex, despair, deceit and greed without losing a sense of innocence, but it’s not an easy thing to do.

Harry Langdon and Joan Crawford in Tramp Tramp Tramp (directed by Harry Edwards), 1926

break

What if you’ve already lost your sense of innocence, though? You’re not alone. At the beginning of this post, I mentioned how I secretly wanted to inhabit Frank Capra’s cinematic realm. Who wouldn’t want to be a part of a world where most characters radiate folksy charm and goodness, the mothers and fathers love each other, the kids are rambunctious but cheerful, and everyone knows each other by name, even the maids and taxi drivers. The only problem is that I knew even as a youngster that Capra would not have cast me in his films. I was too tangled up inside.

My family did the best they could, but there was a bit of screaming when no one else was around, and I didn’t handle it well. In school, I was the chubby kid who didn’t know how to defend himself, so people picked on me to the point where I’d come home crying and count the number of days left in the school year. (I’m better at defending myself now. If possible I’d prefer not to fight, but I don’t fear conflict.)

Photo credit: flickr.com/library_of_congress, 1941

break

Anyway, I chose to let those sour ingredients ferment inside my heart, and slowly I grew up a little crooked. I tried to hide the things in my soul that weren’t as they should be by being a good student and striving to get the outward appearances right. Sometimes, I even tried to be earnest like Capra’s actors, but I came across as muddled and disingenuous. When you can’t even be honest with yourself about who you are, then it’s much harder to convince others of your sincerity.

Lamentably, there are still things I do on occasion that don’t mesh with the Capra ideal. I’m doing the best I can to live better, but it still stings to admit that. Now and then when I’m confused about how to handle a challenge in my life, I’ll ask myself, “What would Capra do?” To admire someone but to know that you probably don’t live up to all of his standards is a conflicting experience, to say the least. Still, I have reason to think that I wouldn’t be entirely scorned by Capra.

Meet John Doe and State of the Union both feature men who sold out but who are struggling to redeem themselves. Lest you think I’m reading too much into the films, consider Spencer Tracy’s quote from State of the Union, “I sold out to them, but get this straight, I am no lamb led to the slaughter. I ran to it.” Still, just like Gary Cooper in Meet John Doe, Tracy gets to set things right after he acknowledges his errors. Capra believes in second chances.

The last movie Capra made was Pocketful of Miracles, which is a remake of his earlier Lady for a Day. The story involves a gangster who is given the chance to help a beggar lady by getting his goons to act like high class people.

Getting lowlifes to appear cultured can be part of a director’s job as well, and maybe that’s why Capra liked the story enough to revisit it. (If you don’t know what I mean, try spending a little more time around actors! I’m saying that as someone who has, on a few rare occasions, gotten paid to act.) It’s possible, though, that Capra connected with the story because it offers even a gangster the chance to become a decent person.

Photo credit: flickr.com/uw_digital_images, ca. 1929-1932

break

The decisions Capra characters make in the past aren’t nearly as dramatically significant as the choices they make in the present. I’d like to think that is Capra’s way of offering hope to those of us who have already lost our sense of innocence but are trying to rediscover it.

In the course of preparing for this post, I ran into another instance where I found myself wondering what Capra would do. It came after watching Glenn Beck’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial. After seeing it and hearing about the criticism he received, something inside my heart told me I should defend him. I did not wish to do so. Every time I speak out politically I threaten my ability to work in the film industry, since a strong majority of filmmakers think differently than I do.

I’ve spoken out before, but this time it felt like there was more at stake. This time I had a sense that I was close to attaining something very dear to my heart, something I’ve pursued for months and even years of my life, and that I might ruin things by speaking up. Maybe it was just my imagination. I don’t know, but the things I sense tend to have some connection to reality.

Angrily, I pushed the idea of defending Glenn Beck away, but a voice in my head kept asking me what Capra would do. The only way to avoid that question was to give up on this post. I tried that too, but I kept coming back to the same question. Avoiding the question in the name convenience is not the Capra way, after all.

Finally, I answered: Capra would do the right thing because it was the right thing to do, regardless of the cost. But I still had a way out: I wasn’t entirely sure that defending Glenn Beck was the right thing to do. I asked God to make it clear if I should speak up, and God made it clear (at least as clear as anything can be that involves divine revelation, which is to say that there is still room for doubt and that pressing forward still involves faith, but I got more than what was statistically probable).

I did defend Glenn Beck, and I don’t know what will happen because of that, but I might not have made that decision if it weren’t for the influence of Frank Capra, a man I’ve never met. As Clarence Oddbody the Angel might say, “Strange, isn’t it? Each man’s life touches so many other lives.”

Photo credit: flickr.com/george_eastman_house, 1945

break

I’m still praying that things will work out. If you’re up there reading this Mr. Capra, then I could use your help. I’m not Catholic, but I’ll campaign to get you sainted, if the secret wishes in my heart come true in part because of you.

Since Frank Capra preferred the popular over the pretentious and liked to end his films with a stirring bit of music, I think these lyrics from Lee Ann Womack’s song are a fitting way to end this Capra tribute:

“I hope you never fear those mountains in the distance

Never settle for the path of least resistance

Living might mean taking chances

But they’re worth taking

Lovin’ might be a mistake

But it’s worth making

Don’t let some hell bent heart

Leave you bitter

When you come close to selling out

Reconsider

Give the heavens above

More than just a passing glance

And when you get the choice to sit it out or dance

I hope you dance.”

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons, 1943

break

Thanks for reading, and God bless.

(If you’ve enjoyed reading this post or some of the others I’ve written, consider signing up to get my posts by email. You can do that by clicking here. I don’t write every week. I only write when I have something worth writing and after I’ve spent some time considering my subject and finessing my thoughts. If you’re following along by email, you’ll know right away when I have a new post waiting for you, whether that’s next week or a month from now.)