This is the end

Hold your breath and count to ten

Feel the earth move and then

Hear my heart burst again

For this is the end

To the uninitiated, that is the beginning of the theme song from the 23rd James Bond film. To quote Adele, Skyfall is where we start, but how exactly does James Dean relate to the latest iteration of James Bond?

Well, James Dean does have a name that is not unlike that of England’s secret agent man, but it is not just that. The number 23 also has a certain significance to the James Dean story, but it is not just that. I’ll explain eventually.

James Dean at Palm Springs in Speedster 23F – March 1955. © Chad White

(This photo has exclusive copyright use in the book James Dean At Speed by Lee Raskin. Special thanks to Mr. Raskin for allowing it to be included here for educational purposes.)

To explain I will reference another film in which James Dean was not involved. The film in question does involve another James though, well actually Jim, as in Jim Carrey, but Jim and James are interchangeable names as far as most people are concerned. That is not to say that I will also be discussing Jimmy Dean, the maker of assorted sausages. Jimmy Dean sausages, while delicious, do not relate to the story at hand.

This is not going to be the typical James Dean write up, but for the first time ever on the nsavides blog, I have something to offer the hobbyist and professional numerologists out there! So gather around and tell your friends, well if you have friends who happen to be numerology enthusiasts, that is.

From the “Torn Sweater” series – Roy Schatt, 1954

For three years after his death, James Dean received more fan mail than any other living star at the time. Thousands of fans have made a pilgrimage to his tombstone in Fairmount, Indiana, and the annual James Dean Festival is still a well attended event.

In the 1970s a businessman in Japan commissioned a James Dean sculpture memorial to be placed less than a mile from where James Dean died, testifying to James Dean’s global appeal.

His admirers are not even limited to the past and present. In the future, Starfleet Lieutenant Commander Tom Paris will list James Dean as one of 20th-century-Earth’s greatest actors. We know this because the fates have given us Star Trek.

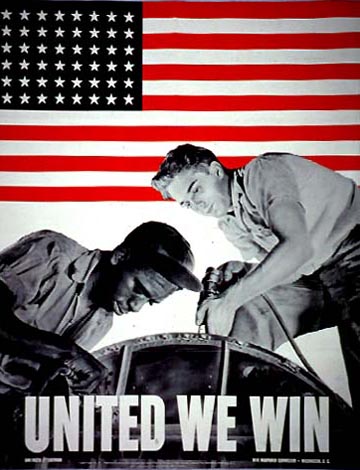

Dean helped to crystallize the emerging youth culture, giving rise to the notion that teenagers were somehow separate from the culture and values of their parents. Prior to James Dean, teenagers dressed like they this:

Now they dress more like this:

John Lennon said, “I suppose you could say that without James Dean, the Beatles would never have existed.” Plus, James Dean’s brand of sensitive masculinity made possible the careers of actors like Jake Gyllenhaal, Ryan Gosling, and James Franco. (Acknowledging the debt, James Franco played Dean in the 2001 made-for-TV biopic. More on that later.) Nicholas Cage went so far as to thank James Dean first when he won his Oscar for Leaving Los Vegas.

I could spend pages exploring the influence that James Dean had on others, but instead I will focus mostly on the influence that he had on me. It’s more personal that way. The work from others that I find most compelling is the personal sort, so I hope that you can forgive me for talking about myself in the context of a screen legend.

My intention is not to convince you that I am the next James Dean. I am in many ways very different. To state just one obvious distinction, I am still struggling to find my way in the world and to refine my abilities, whatever they may be, while James Dean is widely regarded to be among the finest actors of his generation.

Rather, my intention is to explore the universal appeal of James Dean by exploring his impact on me. The personal approach sometimes illuminates truths that would otherwise remain hidden, and that’s the goal here.

With that said, I have done some research, and I will discuss his films in detail, so even if you care very little about me, you might still learn something. Fair enough?

James Dean with cousin Markie – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

James Dean was involved in a handful of TV productions, but he made only three films before he died. I will discuss all three, so I encourage you to watch them before proceeding. They are all masterpieces, arguably some of the best films ever made: East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, and Giant. Go ahead and watch Skyfall as well. I will discuss that one too.

Before going further, I should mention that this is my first substantial writing project after two incidents that crippled my creative capacities for days, and I’m still a little sore.

The first incident is the recent Newtown shooting. Why should I spend so much time writing something of limited appeal, when there is such evil in our midst, I wondered. I was working on this subject before the shooting, but after it happened I found myself wondering, “Can a celebrity from the 50s still be relevant in times like these?”

The best I can do for an answer is to say that it feels like I should still write and that I get something out of writing even if no one else does.

As it happens, James Dean was 24 years old when died, the same age as the shooter at Newtown. (Correction: the shooter at Newtown was actually 20 years old. An initial report I had read listed him as being 24.) One young man left only devastation in his wake. In stark contrast, James Dean left the world with thousands of admirers. Maybe there is something relevant about James Dean even in our troubled times, after all.

Guess who else is 24? That would Adele, singer of Skyfall.

James Dean with rifle in Fairmount – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

The second incident in question is hard to describe succinctly, but let us just say that I spent years of my life pursuing a possibility close to my heart only to see it crumble and devolve into a situation where people I once admired and depended on to do the right thing went out of their way to hurt me with maliciousness. At the very least they were indifferent to the anguish they caused me.

It is not quite the same thing as losing a child in a horrific shooting, I know. The affected families are stronger than I am. I don’t think I could be gracious to others, in the way they have been, after my child had been shot. I admire their resilience, and I will keep them in my prayers.

Nor did I get shot off a train while plunging into a watery abyss as happens to James Bond at the start of Skyfall, but that’s sort of how it felt. My heartache is small in the grand scheme of things, but that doesn’t make it sting any less. Even so, I am back on my feet again. Bear with me: My aim is still a little clumsy, but I’m doing the best I can.

James Dean with Dad in wartime uniform

To say that the James Dean films involve father issues is putting it mildly. Take out the drama with dad in East of Eden and Rebel Without A Cause and you have no story. I will even make the case that father issues are also part of Dean’s character in Giant, although that is less apparent.

It is almost as if Dean’s appearance in the popular TV sitcom Trouble with Father early in his career was meant to foreshadow the direction his career would later take. As I will point out later in this post, that’s not the only time when James Dean’s work somehow foreshadows later events in his life. Sometimes reality is stranger than fiction.

Was it just shrewd branding on Dean’s part that drove him to pursue roles that involve daddy issues? Wes D. Gehring, one of Dean’s biographers, seems to think so. In his book Rebel With a Cause, Gehring quotes locals from Fairmount, Indiana, who describe James Dean as a happy-go-lucky kid. Gehring builds his case by referencing James Dean’s more calculating moments: he asked his agent whether dating someone would help his career, some of his friends observed him acting differently when around fans, and so on.

When James Dean was still alive, he was associated with authenticity, a sort of real-life extension of Holden Caulfield from J.D. Salinger’s novel Catcher in the Rye (1951). If James Dean was just another Hollywood phony though, then that would severely undercut much of what he represents, so let’s explore that possibility.

Hollywood phonies are everywhere, and complicit media companies expand their influence. This music video from Evanscence is here to illustrate:

Since we’re on the subject, let’s talk a little bit about the celebrity reaction to the horrible Newtown tragedy. I was saddened when I heard about it, and I spent some time reflecting on what happened. What can we do better as a society? What can I do better? I had lots of thoughts, but scoring political points or insulting others not involved was the last thing on my mind. Not so for certain celebrities.

Here is the solution Kevin Williamson offered on Twitter: “We need gun control. Stop defending your right to bear arms. You’re stupid.” Got to say, that’s not the most persuasive thing I’ve ever read.

While I agree that having some nuanced laws about guns can be beneficial, Connecticut already has stringent gun control laws on the books, some of which the shooter broke.

Kevin Williamson happens to be the creator behind the massively profitable Scream franchise, a series so violent that it almost received an NC-17 rating. The Scream mask was a popular Halloween costume for years, and it gave a certain cultural cachet to dressing up as and pretending to be a serial killer.

Where do those crazy kids get all those crazy ideas? Since Kevin Williamson mentions an obsession with serial killers on his Twitter profile, perhaps he has some special insight on this.

But hey, the killers in Kevin’s films use knives, whereas the killer used a gun in Newtown. That is different.

I’m not saying that violent films cause violent crimes, but they can influence killers, just as anything can. Advertisements don’t cause you to buy things, but they do influence your buying habits. To argue that advertisements influence choices but films and music do not is just wishful thinking. Look at all the kids who imitate the styles and mannerisms of the celebrities on the big screen. Imitation doesn’t stop at style, folks.

Remember, the shooters at Columbine watched Natural Born Killers repeatedly before going on their killing spree. For whatever reason they chose not to prepare by watching Disney’s Pinocchio or Mozart’s Così fan tutte.

Back in the day, I did enjoy Dawson’s Creek, so I will give Kevin Williamson the benefit of the doubt, but perhaps more self reflection and less finger pointing is in order. I say that as someone who has done quite a bit of soul searching lately myself.

In regards to Dawson’s Creek, I’m curious if the name is a reference to Dawson High in Rebel Without a Cause. It would make sense. Dawson’s Creek brings to mind Rebel Without a Cause in the way it explores the struggles of suburban teenagers while striving for a sense of innocence.

Still from Rebel Without a Cause – 1955

And with that we are back to James Dean. As far as I can tell, James Dean never pulled a Kevin Williamson. The closest he came to that sort of thing was participating in a public safety video about driving carefully even though he had a tendency to speed, but he acknowledges his racing background in the spot. To urge caution is not quite the same as insulting others for believing in a core Constitutional right.

Anyway, I do understand Wes D. Gehring’s apprehension about James Dean. I’ve been fooled by celebrities on more than one occasion, but I don’t believe that James Dean was just another Hollywood phony.

While presenting his interpretation of Dean, Gehring downplays the fact that James Dean lost his mother at the age of 9. When she died, James was sent to live with his aunt and uncle in Fairmount. That’s when his father Winton severed ties. While James would try to reach out to him over the years, Winton kept his distance.

Gehring acknowledges as much, but he treats it as a mere trifle. Yes, his mother died when James was young, and yes his father wanted nothing to do with him after she died, but look at how happy he was growing up in Indiana, Gehring argues.

James Dean, New York City – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

The photo was part of a photo essay Dennis Stock did for LIFE magazine. Along with Dean’s 3 films, Stock’s photos played a significant role in turning James Dean into the cultural icon that he’s become.

I don’t buy it. For one thing, Gehring is himself from Indiana, and he paints the state as a bucolic little place where it is basically impossible to be unhappy. Sounds like a great state to visit, but surely it is possible to be unhappy even in small-town Indiana, even without the neighbors noticing.

Most of the time when people are unhappy, they go out of their way to hide that information from others. If that weren’t true, think how easy it would be to predict divorce: “Oh Beatrice, thank you for the lovely Christmas card, but you look like you’re going to throw up when you’re standing next to your husband. Have you seen a doctor?” Etc.

Nor is it not surprising that James Dean had a manipulative side. You could say that actors are in the manipulation business, after all. Ask me on a good day, and I might say that actors are in the business of telling the truth in imaginative ways, but that opinion is subject to change depending on the actors with whom I interact.

Show business is a very competitive business, and when your very survival seems threatened by powerful forces beyond your control, it becomes more challenging to always take the high road. Still, it is an oversimplification to reduce James Dean to a Machiavellian careerist. Consider that James Dean did not attend the East of Eden premiere in New York, even though his absence greatly displeased Jack Warner, the studio mogul who could make or break his career.

James didn’t attend the East of Eden premiere, but some people still came.

Some celebrities perk up when doing behind-the-scenes interviews. These moments are gifted to them by the very Muses that grace Mount Helicon, they believe. For after all, they are bestowed with the divine opportunity to talk about themselves and their dedication to their craft, both of which are glorious. James Dean is not like that in his interviews. He has this indifferent manner that comes across as something like, “I could care less about this. This is not what I want. Not really.”

That could be just an act, sure, but there are a few stories out there that suggest otherwise.

Leonard Rosenman, the composer for Rebel without a Cause, tells a revealing story about how James would keep asking him to play basketball. Rosenman was not a sports guy, so the requests irritated him. One day he got angry and demanded to know why it was such a big deal to play basketball. Jimmy tried to explain by saying, “It’s like you want your father to play ball with you.” This made Rosenman angrier, and that was the breaking point of their friendship.

I can relate to that.

I was in college, studying film at Boston University. I had a hard time connecting with most of my professors, but one of my film professors made me feel like he wasn’t just doing a job; he seemed to care about us in general, and me in particular.

That professor wasn’t one of those bores who only talks about obscure and pretentious films. He also spent some time discussing the notion of a moral universe and how dramas reinforce or test that notion in various ways. I had not encountered anything quite like that before, and I was captivated.

As fate would have it, he was also who expanded my appreciation for Cameron Crowe’s films and my first professor to discuss how our relationships with our fathers can shape our lives in significant ways.

At the time, my relationship with my father was non-existent at best. If pressed to describe a key childhood memory with him, I would describe an empty office. Some guys talk about how disappointed they were when their dads could not make it to see them play a big game. I don’t remember my dad coming to see any of my games. Maybe he came to one when I was 11 or 12. I’m not sure.

It’s not that he was too busy or travelling somewhere for work. He was at home, but he preferred to spend the weekend sleeping. That’s how he spent every weekend. Literally every weekend. The times we did interact were either confrontational or filled with superficial pleasantries.

I didn’t realize until years later that my dad was doing the best he could, that he treated me the way he did in large part because he never got over the unjust treatment his family inflicted upon him when he was younger.

Anyway, when my professor challenged us to consider our lives in context to our relationships with our fathers, I finally had some way to explain why my relationships with others tended to be distant or non existent. This gave me some hope, and as a result I came to see my professor as a kind of father figure.

When I asked him to read a screenplay I had written, I wasn’t really asking him to read it because he was well connected. I was asking him to take some interest in something I did, but at the time I could not admit that to him or even to myself.

That interaction went badly. It ended in an email where he told me that it would be best for both of us if we never spoke to each other again. He was half right about that: It was better for him, I think. Several months later I went to the Cannes Film Festival as student volunteer with Kodak. I drank so much that I ended up in the hospital. At the time I convinced myself I did that because it didn’t work out with a girl, but it was not about a girl. Not really.

James Dean doing his best Marlon Brando – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

I haven’t read every James Dean book out there, but I read a few of them and watched a few documentaries. I couldn’t find a single one that provided a satisfactory explanation as to why Dean’s father Winton stayed away. The James Dean biopic with James Franco that I mentioned earlier made this the central dramatic question. Almost everything in the film matches exactly with the information I discovered about James Dean, but as far as I can tell, Winton’s explanation in the film is a fabrication. The film suggests as much in the closing credits: “Most of this film was based on fact… some was an educated guess.”

Still, I was relieved to discover that not everyone shares Gehring’s skepticism about James Dean. Mark Rydell, the director of the James Dean biopic had this to say, “The truth of the matter is that Jimmy was haunted throughout his life, his short life, by his need for a father.” William Bast, Screenwriter and friend to James Dean, echoed that sentiment, “The roles he was getting were very much related to his actual life and to his psychological involvements.”

My take on Dean is that he became synonymous with authenticity because his work did not contradict the things he said or the way he lived his life and because he had the courage to expose his wounds in his work. He didn’t do that from the start of his career, but he grew into that capacity over time.

James Dean’s first taste of acclaim came when he performed A Madman’s Manuscript for the National Forensic League while he was still in school. No, contrary to what you might have heard he was NOT doing a speech from the popular AMC show about advertising men.

James Dean might have been ahead of his time, but he wasn’t that far ahead! His Madman monologue was instead taken from a segment in Chapter 11 of Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers. He would go on to perform that monologue at the national level. There he lost on a technicality, but his interest in the performing arts had been cemented.

While Jimmy did not have the good fortune of being in Mad Men, his first appearance on television was for this Pepsi Cola commercial:

“Pepsi Cola hits the spot! More bounce to the ounce! More bounce to the ounce!” Oh right. I guess we should get on with it. Sorry about that. It is a catchy jiggle though, right? I think even Don Draper might approve.

Dean’s TV work hints of the greatness to come. His fluidity and dynamic range is apparent even in his early roles, and TV work gave him the experience to knock it out of the park when he would move on to film.

While none of Jame Dean’s work on television is considered masterpiece quality, he did get the chance to act alongside future President Ronald Reagan in “The Dark, Dark Hour,” which he filmed after East of Eden. To be fair, television was still considered a new medium at the time. It would take another decade or two before TV would seriously compete with film for artistic laurels.

Since James Dean did share time with Reagan onscreen it seems appropriate that Dean’s one notable political comment is virilely anti-Communist in nature: “I hate anything that limits progress or growth. I hate institutions that do this, a way of acting that limits [creativity, or], a way of thinking. I hope this doesn’t make me sound like a Communist. Communism is the most limiting factor of all today: if you really want to put the screws on yourself.”

That James Dean had a good head on his shoulders. Sorry comrades, James Dean was no spread-the-wealth occupier.

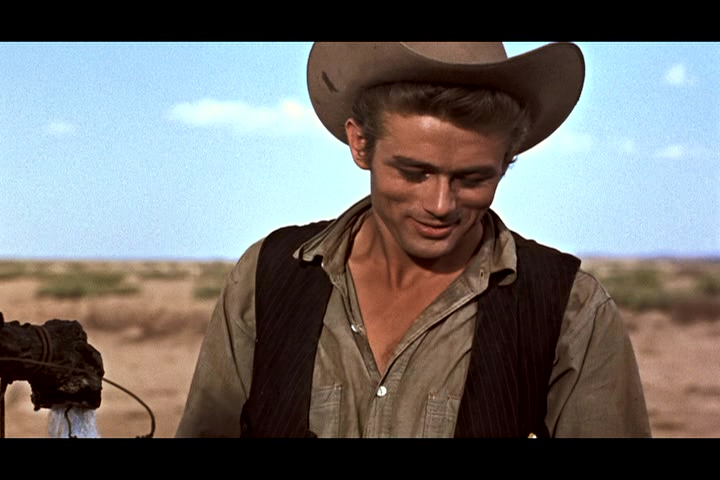

James Dean was just 23 years old when he made East of Eden, and that’s the film that first made him famous. Incidentally, Bob Dylan, a big James Dean fan, was 23 when he released “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” the first song that made him famous. (That’s the one with the notecards in the documentary Don’t Look Back.)

Here’s a fun fact: Don McLean’s song “American Pie” has a line in it that is widely interpreted as a reference to Bob Dylan’s enthusiasm for channeling Dean: “The Jester sings for the king and queen in a coat he borrowed from James Dean.” Let’s take a look:

James Dean – Walking Down Street – Roy Schatt, 1954

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan – 1963

Can you spot the similarities? Remember this post is not just about James Dean, but about the influence he had on others, and I think it’s fair to say that Bob Dylan borrowed more than just a coat from James Dean. Writer George Perry went so far as to speculate that Bob Dylan was thinking of James Dean when he wrote “Forever Young.”

Although he was just 23 at the time, Dean delivered a powerful, gut wrenching performance in East of Eden, the film billed for good reason as “The Searing Classic of Paradise Lost.” Film critic Pauline Kael said of the film “a boy’s agonies should not be dwelt on so lovingly: being misunderstood may easily become the new and glamorous lyricism.”

The scene where Dean’s character Cal Trask falls apart when his father rejects the money Cal earned is one of the most powerful scenes ever put to film, and the power comes from the vulnerability that James brings.

James Dean’s big scene with Raymond Massey in East of Eden, 1955.

This was something new. Up until that time, leading men were the strong and stoic types like Humprey Bogart, the charming gentleman like Cary Grant, or the likable everyman like James Stewart. But the wounded young man who weeps uncontrollably when cut to the core? That was different.

Like James Dean, Marlon Brando came from the Actor’s Studio in New York, co-founded by East of Eden director Elia Kazan, but Brando’s interpretation of method acting was more volatile, more agressive. James Dean’s interpretation involves more vulnerability, but he still comes across as masculine, and that was what made his performance all the more astonishing.

While Dean’s Cal is called bad by the other characters, he is dressed in all white for most of the film. This is intentional. As Eli Kazan explains, “I wanted to show that a boy whom people thought was bad was really good.”

James Dean as Cal Trask in East of Eden, 1955.

That is not to say that Dean is playing every scene with seeping emotion. Go back and watch the scene with him and Julie Harris in the meadow. Julie’s character Abra teases Cal about the other girls in his life, to which he responds with bemused nonchalance, but as Abra tells him about her own background his attitude changes somewhat. It isn’t until she declares that she doesn’t like her father’s new wife much because “she’s a woman” that James Dean has to move away.

Abra has just told Cal that she can relate to him because he cares more about winning the affection of his father than the affection of another girl, although he has never admitted as much. Now that he feels exposed, his playful swagger is gone. It’s a brilliant moment handled with subtlety.

There is also some interesting subtext in the film that is worth mentioning. Cal goes to a businessman Mr. Hamilton to borrow some money, and he ends up standing in front of locker 23 as he negotiates. Mr. Hamilton is taking a shower and then dries off. When Cal approaches, Mr. Hamilton says “Don’t get so near me. I don’t want to get all hot again.” Mr. Hamilton is still in the process of getting dressed as he delivers that line. Hmm.

Even in that scene James Dean adds little physical flourishes, like rubbing his nose against the locker in a seemingly casual way that nicely complements the scene. It’s the kind of gesture that most actors wouldn’t bother with because it seems so trivial, but it is exactly right for the moment.

Later in the film, Cal’s mother wonders why Mr. Hamilton would go into business with Cal even though Cal doesn’t have much experience. “Maybe he likes you,” she says. Hmm.

Jo Van Fleet plays mom to James Dean in East of Eden. Note how her hat makes her look kind of witchlike.

Abra’s speech at the end ties it all together: “It’s awful not to be loved. It’s the worst thing in the world. Don’t ask me how I know that. I just know it. Makes you mean and violent and cruel, and that’s the way Cal felt all his life. I know you didn’t mean it to be that way, but it’s true. You never gave him your love. You never asked him for his. You never asked him for one thing. You have to give him some sign that you love him, or else he’ll never be a man. He’ll just keep on feeling guilty and alone unless you release him. Please help him. I love Cal, Mr. Trask, and I want him to be whole and strong, and you’re the only one who can do it. Try. Please Try. ”

James Dean and Julie Harris – East of Eden, 1955

Abra (cadabra), the girl works her magic, and Mr. Trask does ask his son for something. The implication is that Cal will finally heal and become the man he was meant to be. Not every critic likes the ending, but I do. It gives the James Dean needed closure that he never quite found in his real life.

You know, there’s another film where the girl helps the guy become a man. In that one she’s removing a pink mask from his face. Which one is it again? It’s Sky something … Sky Captain? Skydive? Skyfall? Wait, that’s the James Bond one. Oh well.

Thanks to the fantasy that filmmaking allowed, James Dean had a brief sense of reconciliation with his father, albeit a fictional one. When East of Eden finished shooting, James Dean was found crying. “It’s over,” he lamented.

Opening to Rebel Without a Cause.

In Rebel without a Cause, it is not just James Dean’s character, Jim Stark, who has father issues. It’s the central hangup for Judy (Natalie Wood) and Sal Mineo (Plato) as well.

When Judy goes to kiss her father, he slaps her away. We are meant to understand that is the reason why she bemoans, “I’ll never get close to anyone.” Plato goes so far as to keep a photo of his dad in his locker. After school he rushes home, eagerly anticipating a letter from dad. When the letter finally arrives, it reveals the dad’s lack of interest, and Plato is heartbroken.

At the beginning of the film, Jim is in custody and his father tries to understand why. “Don’t I buy you everything you want,” he asks Jim, as if that should be enough to keep Jim out of trouble.

Later when Jim is in crisis, he goes to his dad looking for guidance, but his apron-wearing dad offers little of substance, reiterating his appeasing approach to parenting: “Did I ever stop you from anything,” he asks Jim. That’s not what Jim wants to hear.

Jim Backus plays dad to Jim – Rebel Without a Cause, 1955.

When his overbearing mother returns, Jim pleads with his dad to defend him: “Dad stand up for me.” Intimidated by mother, dad does nothing, and Jim leaves angry and determined to resolve things on his own.

Because his dad won’t stand up for him, Jim has to go and do something reckless to feel more like a man. Because she is scorned by her dad, Judy is cruel to Jim, even though he is trying to be nice to her. Jim has to prove his affection comes from strength before she lets her guard down.

Still from Rebel Without a Cause – 1955

In the end, it takes the death of Plato for Jim’s father to finally stand up for Jim. Only then does he tell his devastated son, “Jim, you can depend on me. Trust me. Whatever comes we’ll face it together” and “I’ll try to be as strong as you want me to be.” He helps Jim stand up, and they walk away together. Just like in East of Eden, the dad finally takes action to help his son become a man.

How refreshing to watch a film about teenagers that is actually interested in their inner lives. In contrast, today’s typical teenage films are all spectacle and sex: When will the hot girl strip? In Act I, Act II, or Act III? Which horny douchebag will get to bang her? Ah, progress! Right?

To quote the new James Bond film, “Sometimes the old ways are the best.” What else would you expect from a film that quotes from Shakespeare’s The Tempest?!

(Not all the contemporary teenage films are like that. In the Twilight series, the story is driven by relationship dynamics rather than stripper enthusiasm, which is why I defend the series in spite of the flack my guy friends give me.)

In Rebel Without a Cause Dean once again plays the vulnerable tough guy, and once again his outfit is symbolic. Dressed in red, white, and blue, James Dean is the all-American boy, the face of troubled teenagers in suburbia everywhere, and his performance is even more fluid than in East of Eden.

Watch how he goes from drunken confusion to tender concern as he covers the toy monkey at the beginning of the film. Watch how quickly he goes from tears to laughter and back as he spots Plato’s mismatched socks at the end of the film.

In the observatory scene before Plato gets shot, the three kids reimagine themselves as a happy family. Remember that song, “Jack and Diane” by John Mellencamp? When John does his best James Dean, he’s imitating James at the observatory.

Rebel’s screenwriter Stewart Stern explains that the observatory scene is meant to represent a kind of Neverland, where Jim and Judy become Peter and Wendy, and Plato assumes the part of the lost boy. It’s as if they have to escape the phony material-minded world of their parents to be able to envision a happy family.

Dylan does his best James Dean.

It is interesting though that the three kids reimagine themselves as a happy family, as opposed to bohemian revolutionaries living on a commune. That brings to mind something Natalie Wood said in an interview. She explained that James Dean was not entirely a rebel but that he also craved the kind of connection that comes with a traditional way of living. Composer Leonard Rosenman agreed: “Jimmy had actually a kind of conservative fantasy about what he wanted to do. He wanted tranquility, he wanted to create in some way, he wanted to be a kind of an intellectual.”

Observatory scene in Rebel Without a Cause, 1955.

It seems that James Dean did some experimenting as far as relationships go, but he also appeared to be distraught when things did not work out with his girlfriend Pier Angeli. Her mother insisted that she marry a respectable Roman Catholic instead, and James Dean is reported to have revved his motorcycle loudly in protest when she and Vic Damone emerged from the church as newlyweds.

One more story about Rebel, and then we’ll look at Giant. Jim fights a guy because he calls him chicken and then agrees to take part in a dangerous race. Back to the Future fans will recall that was also what riled Marty McFly into racing, which caused an accident that ruined his future. Thanks to a warning from Doc, Marty goes back to 1955 in an effort to make things right. Notably, 1955 was the year that James Dean had his tragic accident, so it is a bittersweet tribute.

Why didn’t James Dean get a warning? Why didn’t Jimmy get a chance to change things? Actually, I think he did. We’ll get to that soon enough. Hang in there, numerology enthusiasts!

Giant was Dean’s last film. This time, he plays the bad guy, Jett Rink. There he is below, covered in black oil, ready to stain the world with his impetuous disdain.

James Dean as Jett Rink in Giant, 1956.

The oil Jett discovers on his land makes him part of the nouveau riche, but Jett never learns manners, never overcomes his racism, and so he ends the film as he begins: alone. Early in the film, Director George Stevens introduces Jett in a few shots like the ones below.

This shot of a festive crowd is followed by…

this shot of Jett alone:

The last time we see James Dean is in a scene that looks like this:

This has been called Jett’s “Last Supper” scene, a haunting description since it would be the last time audiences would see James Dean in a film. Filming for that scene concluded on September 10th, 1955. In less than a month, James Dean would be dead.

That shot does provide interesting contrast to Di Vinci’s painting, does it not?

When he is still a ranch hand working for the Benedicts, Jett sees the inherent racism and points it out to Leslie, played by 23-year-old Elizabeth Taylor. It is not that Jett is himself opposed to racism. He perpetuates racism when he becomes a wealthy tycoon. Rather, he is merely looking for a way to undermine Bick Benedict.

Toward the end of the film, Jett is trying to seduce Bick Benedict’s daughter, but the seduction is half-hearted. So much so that the girl has to ask if he is actually proposing. This is how James Dean is lit when he proposes:

That might be the most unromantic lighting for a wedding proposal ever captured on film. Jett seems to be more interested in marrying her because it would give him access to the Benedict family and not for any romantic reason. It’s his last attempt to undermine the Benedict family, a family that he could never really join.

In that way Jett Rink is like Mordred, the illegitimate son of King Arthur. As a reminder, Morded was the stain on Camelot, the result of Arthur’s incestuous relationship with his half sister, brought about by dark magic. Camelot had become a place where might fights for right, so Mordred could never be apart of it. Angered by his exclusion, Mordred vowed to destroy his father and the kingdom he built, but in so doing Mordred destroys himself in the process. That is Jett Rink to a T.

“Sir Mordred” – H. J. Ford, 1902

So even Giant involves a conflict with father, although it is not as explicit as in East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause. But then we do see hints of the father-son conflict in the clashes of acting styles between classically trained Rock Hudson and method actor James Dean.

The father-son conflict was more apparent behind the scenes between James Dean and George Stevens. Before going to work on Giant, James Dean had only the highest praise for George Stevens: “George Stevens, for my money, is the greatest director of them all – even greater than Kazan.” (I agree with James that George Stevens is one of the greatest directors of all time.)

On set, it was a different story. James would throw tantrums and storm off set when he felt that George Stevens was taking too long to set up. In the James Dean biopic with James Franco, there is speculation that the tension arose because George Stevens somehow reminded James Dean of his own father. That seems plausible.

Jame Dean’s last day on Giant was September 23, 1955. Here’s where it gets interesting. Two credible sources claimed to have warned him about driving his new Porsche 550 Spyder on that day.

James Dean at Mobile Station, Sherman Oaks on the day of the accident. photo by Rolf Wutherich, 1955

Here’s what George Stevens claims he told James Dean that day: “‘You can never drive this car on the lot again; You’re gonna kill a carpenter or an actor or somebody.’ And that was the last time I saw Jimmy.”

And then there is that quote from Alec Guinness, mentioned in his autobiography, Blessings in Disguise. Keep in mind this autobiography was published in 1985, long after Guinness had achieved critical acclaim as an actor, so he had very little incentive to fabricate something like this.

When James Dean showed Alec Guinness his new sports car, here’s what Alec Guinness said: “‘Please, never get in it.’ I looked at my watch. ‘It is now ten o’clock, Friday the 23rd of September, 1955. If you get in that car you will be found dead in it by this time next week.'”

One week later, James Dean died in a car crash. Why didn’t you listen to Obi-Wan Kenobi, James? Why?

According to those who knew him, Alec Guinness was not inclined to give such pronouncements. A few months later, Alec Guinness was formally received into the Roman Catholic Church. He does not strike me as a dishonest man, but how strange the James Dean story becomes if Alec Guinness told the truth.

The guy who hit James Dean was Donald Turnupseed, an ex-sailor. At the time Donald Turnupseed was 23 years old.

Have you started to notice how often the number 23 appears in the James Dean story? It showed up enough that I revisited the Jim Carrey’s film The Number 23, a film The New York Times dubbed Carrey’s “accidental comedy.” That’s what I do for you, ladies and gentlemen. I will watch even an accidental comedy to bring you the insights that you’ve come to expect on the nsavides blog!

The Number 23 is only so so as a film, but it draws attention to the enigma of the number 23 that predates the film, and that is more interesting than the film itself.

Before exploring the significance of the number 23, here’s a quick overview of numerology: Ancient cultures believed that numbers have certain mystical associations, sort of like how astrologers look to the stars for clues about destiny. Pythagoras, known to geometry students today for his Pythagorean theorem, believed in numerology. Even Biblical scholars note the recurring appearance of certain numbers throughout the scriptures. Darren Aronofsky’s film Pi explores that tradition in more detail.

Still from Pi – 1998

If we grant that there is indeed a Creator, or even a guiding force like karma that orders the universe, then it does not seem to be such a leap to consider the possibility that certain patterns might be woven into the fabric of it all.

In regards to the number 23, it is the first prime number that contains two consecutive prime numbers, and it has a way of showing up in the course of human events: Each parent contributes 23 chromosomes to a new child, Julius Caesar was stabbed 23 times, William Shakespeare was born and died on April 23rd, The Titanic sank on April 15th, 1912 (4+1+5+ 1+9+1+2), and the Hiroshima bomb was dropped at 8:15 AM (8+15 = 23). September 11, 2001 also adds up (9 + 11 + 2 + 0 + 0+ 1) as does the Apollo 13 launch on 4/11/70 (4+1+1+1+9+7+0), and Apollo 13 was the 23rd American manned space mission.

Some basketball guy seemed to favor the number 23 as well.

Superstruct, the massively multiplayer forecasting game created by the Institue of the Future, predicted that human kind would be extinct in 23 years, and yes the number 23 does show up once or twice in the TV show Lost.

Mathematician John Nash, the man profiled in Ron Howard’s film, A Beautiful Mind, was obsessed with number 23, as was author William Burroughs. The Number 23 was the 23rd film directed by Joel Schumacher, and Jim Carrey believed in the number enough to name his production company JC23 after it.

James Carrey does his best James Dean.

Notable Bible passages involving the number 23:

Numbers 23: 23 Surely there is no enchantment against Jacob, neither is there any divination against Israel: according to this time it shall be said of Jacob and of Israel, What hath God wrought!

Numbers 32: 23 But if ye will not do so, behold, ye have sinned against the Lord: and be sure your sin will find you out.

And of course, there is Psalms 23, a favorite Psalm to people of faith going through difficult times or facing the “valley of the shadow of death.”

Here are a few more notable instances of the number 23 in the James Dean story:

Winton Dean was 23 years old when he met Marion, the gal who would become James Dean’s mother. She died when Dean was 9 at 422 23rd St. Santa Monica, CA.

James Dean was born at the Seven Gables apartment house, 320 East 4th St. in Marion, Indiana. An inverted number still counts to those initiated in the 23 enigma.

In the James Dean 2001 biopic, James sends a package to his father at 815 6th St., Santa Monica, CA (8+15 = 23). A few sources I referenced suggest that Winton’s address was actually 814-B 6th St. It is possible that the film got this detail wrong. Winton’s predecessors did move to Indiana back in 1815, so perhaps the address got mixed up with the family history.

James Dean talking with Ed Kretz at Palm Springs, March 26, 1955. photograph by Gus Vignolle

On Sept. 23rd, 1952, exactly three years before the warning from Alec Guinness, James Dean meets Maila “Vampira” Nurmi, the actresses who played the undead host on The Vampira Show and Plan 9 from Outer Space.

On March 23rd, 1955 James Dean shot his screen test for Rebel Without a Cause with Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo, the only film in which James Dean almost dies in a car crash.

On the day he died, James Dean had just finished shooting Giant and was driving to a race in Salinas, which is where East of Eden was set, so his life ended while travelling to the place where his superstar status began. It gives his career an eerie circular quality. The eeriness doesn’t end there.

James by a tombstone of his ancestor. – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

Note that Cal, the first name on the tombstone, was also the first name of Jame Dean’s character in East of Eden.

The two actors that James Dean most admired were Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift. In his first film, East of Eden, James got to work with Elia Kazan, the director who turned Brando into a star and directed him to an Oscar award for On the Waterfront. In his last film, Giant, James got to work with George Stevens, the director who turned Montgomery Clift into a star and directed him to an Oscar nomination for A Place in the Sun.

James Dean looks a little nervous when his idol Marlon Brando visits ‘East of Eden’ set.

Remember that public service announcement about driving carefully that I mentioned earlier? James Dean shot it while working on Giant, the last film he made before he died:

At the end of the PSA says the words that will forever haunt his story: “Take it easy drivin’… the life you might save might be mine.”

Dennis Stock the photographer responsible for the famous James Dean New York photo was supposed to ride with James to Salinas, but he changed his mind at the last moment.

Incidentally, Dennis Stock also took this photo of James Dean while doing the photo essay for LIFE magazine:

Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

Dennis strongly objected to doing photos of James Dean in a coffin, but James suggested it. Initially James was clowning around in the coffin, but then he grew serious, and that’s when the photo was taken. Here’s what Dennis had to say about it:

“Everything had gone out of Jimmy by then, all the showmanship, all the cuteness. There was nothing there other than a lost person who really doesn’t quite understand why he is doing what he is doing. That’s not a moment to underestimate.” James Dean would be dead in less than 8 months from when that photo was taken.

With all of these coincidences, it is almost as if the story had been scripted by Warner Brothers, the studio that made all three of the James Dean films, but that is unlikely. The studio limited its promotional efforts in response to the tragedy. Studio head Jack Warner was concerned that the accident would hurt the box office: “Nobody will come and see a corpse,” he worried.

Again, two reputable sources claimed to have warned James right before the accident. If an accomplished director like George Stevens and an up-and-coming actor like Alec Guinness both warned you on the same day not to do something, wouldn’t that at least give you pause?

There is evidence to suggest that James Dean even believed in the power of intuition. He once said this to his girlfriend Liz Sheridan about a part for which he auditioned: “I have the strangest feeling. I can’t explain it, but I know I am gonna get it. It’s the strangest feeling I ever had about a job.” He found out later that he did in fact get the part in the play See the Jaguar.

Why didn’t you listen to Alec Guinness, James? Why?

It’s not like the race in Salinas was so important that he couldn’t afford to miss it, but there was something about racing that James could not resist. Before Giant, James Dean had a part in the TV series Crossroads, and once again that seems appropriate.

I believe that James had come to a figurative crossroad in his life, in addition to the literal crossroad where the accident happened. I believe that if James had listened to the warnings, had stepped away from racing for a bit, had stopped running from whatever it was that he was trying to escape, then maybe, just maybe, his life would have taken a different turn.

I can’t prove that, I know, but I can point out all the notable coincidences that surround his death.

Photo copyright John Edgar/Edgar Motorsports, Santa Barbara, May 27, 1955

At one point in his life James Dean did confess that, “racing is the only time I feel whole.” I doubt James would have said that if he wasn’t running from something.

When you’re driving fast you don’t have the luxury of thinking about the things that bother you. You have barely enough time to react to the road ahead.

I can relate to that.

When I was in high school, I accidentally flipped my car into oncoming traffic because I wanted to see how fast I could take a curve. I didn’t know how to get close to people so I would compensate with sensations, and going fast is quite the sensation. It was a mostly empty road, but I missed hitting an oncoming car by a few seconds. For whatever reason, no one got hurt; the car flipped back on to the right side of the road and then slid into a ditch.

These days I try to be a little more cautious, a little more considerate of others, but it is not so easy when my heart is breaking. In case you’re wondering though, I decided I would not drink for the next two months as a preventative measure. That happened after I saw the Denzel Washington film Flight, so that’s one example of when watching a film influenced someone, in this case me, to do something sort of positive.

It’s never been particularly easy for me to get things right, but I am trying.

James Dean plays the congo on the farm. – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

As my detractors will surely point out, I am no James Dean. I don’t want to be. I’m not going to take up smoking, start playing the congo drums, or buy a motorcycle so that I can better imitate him. At best, I could only ever be a second-rate James Dean. I’d rather be a first-rate Nick Savides, but while I’m figuring out how to get there, I don’t see the harm in looking to James Dean for inspiration.

I do connect with him in some ways, in his need to get close to a father figure, in his propensity for speed. James Dean wrote in his journal,”Who am I? I don’t want to be alone. I don’t want to be different. I need people, but I keep pushing them away.” I get that too.

From the “Torn Sweater” series – Roy Schatt, 1954

The Little Prince was one of James Dean’s favorite books. Reading it made him cry. I love that he would give such significance to something that others would dismis as a mere children’s book. When I was a kid, my uncle gave me his copy as a present. It took me a few years to really appreciate it. Now it would be one of the things in my room that I’d grab if my apartment was on fire.

My copy of ‘The Little Prince’

The thing I most admire about James Dean is his generosity in sharing his deepest wounds. By revealing his loneliness, he helps us to feel less alone. By revealing the pain from his absent father, he helps us realize our own need for a father’s affection. His films prod us toward reconnecting with our fathers, if they are still alive, and challenge us to be better fathers, if we have kids.

For most of my life, I was the exact opposite of James Dean: I would do everything possible to avoid showing others how I really felt. It took me so long to get to the point where I could live with an open heart, but then things fell apart, and now it feels like I’m back at square one.

It is possible that if I stay angry about what happened, then the bruises will fester into something ugly. There’s nothing unique there. Everyone faces difficult things, some of us face more difficult things than others. James Dean lost his mom and, for all intents and purposes, his dad at a young age. That could have crippled him as a person if he allowed it to do so, but instead it transformed him into an icon.

The mad islander in Skyfall, played with relish by Javier Bardem, is a testament to what can happen to someone consumed by the hurts of the past. From a distance, mad islander types might look alluring, but get up close and personal and you’ll see a monster, rotting from the inside.

My dad never learned how to get past the wounds that his family inflicted on him when he was a young man. He didn’t become a monster in the mad-islander sense, but he couldn’t be the dad I needed him to be, and that made growing up a little harder.

I don’t know if James Dean ever got over the wounds of the past. I never meet him, and there is only so much I can conclude from a distance. He was courageous enough to face his hurts in his work, but maybe he couldn’t do that in person. James Dean was, after all, known for being difficult on some sets and was nicknamed “the little bastard” by a few of his co-workers. He had that painted on his Porsche, so he wasn’t entirely opposed to the nickname.

James Dean died while driving his “Little Bastard” Porsche. © Sanford Roth/Seita Ohnishi

Back in December 2010, I wrote a positive piece on Cameron Crowe, but I recently read Kicking & Dreaming, a book about the band Heart that was co-written by Cameron’s ex-wife Nancy Wilson. It now seems possible that I was very wrong about Cameron Crowe. In the book, Nancy describes Cameron as someone who was romantic only when they first met and who became detached and more preoccupied with work over time.

As their marriage dissolved, Nancy reveals that she grew more cynical about love: Their marriage ended as anything but a Cameron Crowe film, she confesses. For those keeping score, Kicking & Dreaming was published on Sept 18, 2012 (9 + 1+ 8 + 2 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 2 = 23).

To be fair, an ex-wife is not the most impartial of commentators. Then again, I’ve tried to get in touch with Cameron Crowe for over a year, and from my perspective, he did not treat me in a particularly considerate manner. That’s disappointing, considering how important treating others with consideration is in his films.

In spite of all that, I don’t get a sense that Cameron Crowe is a bad guy. Maybe there is a good explanation, so I will reach out to him to see if I got it wrong or if he wants to set the record straight. I am still a fan, albeit it a more skeptical one.

My point is that someone’s body of work and public persona do not necessarily equate to a person’s character. Maybe James Dean was a good guy. Maybe he wasn’t. I never had the chance to get close enough to find out the truth. That’s why I said that I sort of want to be like him in the title.

I am less ambivalent about wanting to be more like the friends and family who have revealed themselves to be people of character when I see them up close.

Much of what I’ve learned about what it means to be a good man, I’ve learned by watching my uncle, the one who gave me his copy of The Little Prince. (At one point, I proposed doing a blog post about him, but he wasn’t keen on the idea.) I want to be more like him, definitely.

Celebrities are captivating, and occasionally they can make our lives better by sharing their gifts and talents, but they don’t have all the answers either, and they don’t care about us in the way that friends and family can, but it can be hard to remember that when they look so shiny and larger-than-life from a distance.

Still, this post was mostly about James Dean, so let’s say goodbye to him by remembering him at his best: “I’m trying to find the courage to be tender in my life. I know that violent people are weak people. Only the gentle are ever really strong.” With that quote, James Dean brings to mind King David, the original poet warrior who understood, as James Dean did, that the mighty ones are actually those who can approach the giants without armor, even if that means being susceptible to pain, be it physical or emotional.

James Dean with cousin Markie – Dennis Stock, 1955. © Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

We can guard ourselves against pain, and live empty, guarded lives. Or we can embrace life in an open-hearted way, even though there is a real chance that something will come along and knock us down. It might take me a while to live in a truly openhearted way again, but I still opt for the second option.

James Bond has the supernatural ability to get back up and keep fighting even after falling from the sky into a watery tomb. The rest of us need some help in getting back up after life knocks us down. Fortunately there is help to be had, if we look for it in the right place.

While taking in some of the coverage from Newtown, I came across Craig Scott. He’s the brother of Rachel Scott, the first girl who got shot in the Columbine massacre. She’s the one who got shot because she acknowledged her faith in God.

If anyone has an excuse for letting the wounds of the past turn him into a monster, it is Craig Scott. Hateful kids, whom he had never harmed, robbed him of his sister and his friends. Had some punks done that to my sister, I don’t know that I could escape a life hell-bent on vengeance. Craig Scott has instead dedicated his life to reaching out to schools throughout the country, so that he can spread his sister’s belief that a little kindness can go a long way. Everything about his life backs up his outreach. How’s that for authenticity?

Here Craig Scott talks about the Newtown tragedy, how he prevented another school shooting through Rachel’s Challenge, and how our society can counteract such evil.

In this video posted on Aug 23, 2009, Craig Scott reflects on the 10-year anniversary of Columbine:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEIRB0Rhtw4

Learn more about Rachel’s Challenge by visiting the link below:

http://www.rachelschallenge.org/big-picture/about-rachels-challenge

Columbine could have turned him into a monster, but for some inexplicable reason Craig Scott walked through the valley of the shadow of death and emerged as the man who saves lives.

To paraphrase James Bond, “everybody needs a hobby, and Craig Scott’s hobby is resurrection” but Craig doesn’t claim to do it on his own. It is his faith that Craig Scott credits for helping him stand tall even at skyfall.

It was faith too that helped King David write the 23rd Psalm. And so today we can say, “Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord.”

It takes me a little longer to write the kinds of posts I prefer to write, and sometimes my schedule gets complicated, so I can’t promise to have new posts available on a consistent schedule. That’s why I encourage you to sign up by email. You can do that by clicking here.

If you’re following along by email, you’ll know right away when I have a new post waiting for you. It is very easy to unsubscribe, and you won’t receive anything unrelated to my blog.

Lastly, if you appreciate my writing, why not write a comment or share the post with a friend? It would encourage me to keep sharing some of my heart with you.

Merry Christmas everyone, and God bless.