(My apologies for the delayed arrival of this post. Normally I publish a new post each weekend, and do I value consistency and dedication. With that said, this is a time of year that asks much from me and you, and avoiding other people and holiday festivities merely to update this blog on time strikes me as a tragically corporate mistake. For your patience, I am grateful)

If there is any better way to determine the condition of someone’s soul that doesn’t involve their attitude toward giving, then I don’t know what it is. That’s probably why some people put considerable effort into disguising their true sentiments about giving. On the outside, they may be smiling , but in the privacy of their own hearts, they might be hiding obligation, or guilt, or manipulative attempts to get what they want. Others give out of deeply held convictions and genuine affection, wanting nothing in return. It’s not easy to tell what is behind the giving, but then who said it was easy to see a soul as it is and not as it wishes to be seen.

photo from flickr.com/peturgauti

As counter intuitive as it may seem, sometimes the giving involved in charity work is more selfish than the giving involved in being excellent at work. In some circles, doing community service is the best way to gain status and influence. I prove this with the fading bruises I carry from the disdain of girls too preoccupied with missions work to treat me with respect. But then again, on more than one occasion, I volunteered to do community service for the sole reason of meeting girls. (It didn’t work so well; it rarely does when your heart isn’t in the right place.)

It is corporate thinking to assume that everything done on a volunteer basis is noble and good, while everything done to make money is selfish and base. A good employer will pay you based on the results you achieve, so that you have an incentive to aim for excellence. And yet, there are various ways to measure performance, but I don’t know of any system that can accurately track every time an employee or business does more than what the job requires.

Think about the friendly, sincere smile given to the customer who won’t leave any feedback or the way someone spends extra time and effort to get the details right that most people won’t notice. Those kinds of things don’t show up on the annual employee reviews, but some employees still do those things because they want to share kindness and excellence with the world.

Consider also the restaurants that give you larger-than-expected portions or replace the tablecloths and flowers at every table, not just every day, but every few hours. These restaurants could make more money in the short-term by keeping the portions small and opting for plastic flower decorations, but they take pride in giving their guests great atmosphere and a satisfying meal experience. In the long-term, those are the very details that distinguish a restaurant and help it find loyal patrons and financial success, but corporate thinkers tend to avoid this kind of long-term logic and focus only on short-term profit margins and other easily measured statistics.

I’ve read plays like Othello and seen films like the Lord of the Rings several times, but each time I discover something new, and those discoveries surprise and delight me. That only happens when artists like Shakespeare, Hieronymus Bosch, Mozart, and almost everyone at Pixar labor to put elements into their work that most people won’t notice, but they put them in anyway out of a love for their craft and for the particulars of the things they create.

In every Canon digital SLR, even in the entry-level ones, there’s a handful of features that customers will not appreciate unless they have a strong background in photography. Since some consumers lack the experience needed to appreciate such features, Canon could get away with not including them and selling the cameras for a greater short-term profit. But, Canon takes pride in giving optical excellence to the world, and that’s one reason why I’m proud to work for Canon.

photo from flickr.com/andycastro

The artists, craftsman, employees, managers, and entrepreneurs who strive to give the world more than what is expected from the jobs they perform, not out of an exclusive desire for profit, but out of a love and appreciation for excellence, give in a truer way than the self-righteous crones who sometimes pollute the halls of the non-profit organizations they serve. Intention is everything, and the ones who give best, whether they be volunteers or paid professionals, are the ones who would still contribute their gift even if God were the only one watching.

That kind of uncorporate giving doesn’t concern itself too much with how it will be measured and paid back right away. Rather, a sense of faith that some good will come of the effort, guides the gift into fruition. Here’s the secret though: If a worthy gift is given with good intentions, rewards will come whether in financial profit or in a new relationship or in sense of accomplishment, whether in this life or the next, but if you give only to get those rewards, then you’ll never see them.

When you stop and think about it, isn’t a good part of the charm about Christmas decorations found in the fact that they involve a little bit of effort beyond what is expected in daily life? Lights, wreaths, and Christmas trees don’t have to be there, and yet they are, and so they become friendly beacons of goodwill to all who see them. What if people took extra steps to spread a sense of celebration and kindness throughout the year? Wouldn’t that be inspiring in a similar way to Christmas at its best and maybe even in a similarly profitable way?

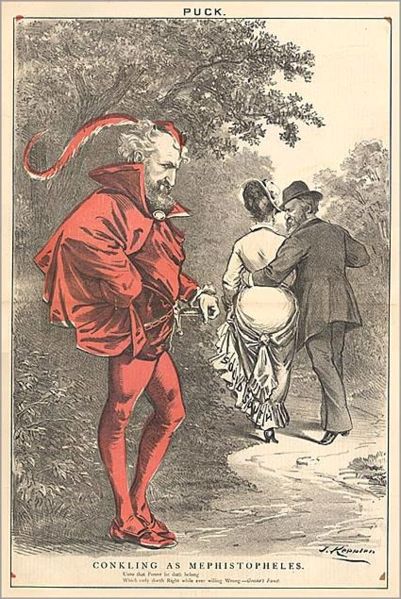

In the nature of disclosure, I should mention that my own attitudes toward giving vary drastically from day to day. Just think of the vast disparity between Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and you’ll get the idea. Some days, I regret to report, my attitude toward giving is essentially this, “well I’d rather burn in hell then help that no-good, dirty, rotten son of a biscuit. (I don’t usually think about biscuits in this context, but for the sake of civility, I’ll take some artistic liberties with the truth. Rest assured though, merry gentlemen and good ladies, the sentiment as a whole is an all too accurate transcription of the thoughts that plague me in my darker days.)

It’s no coincidence that the days where giving seems distasteful to me are the more hellish ones of my existence. The oppressive nature of my own selfishness consumes me and the passage of time becomes an awful, screeching, never ending torment. How much different are the rare days where I re-discover and rest in the love that medieval thinkers called the celestial music of the spheres, the love of God that keeps the planets in harmonious movement and powers every true instance of tenderhearted affection and brotherly love. In those moments I can give graciously and unselfishly, without regard for whether my efforts will be appreciated or reciprocated.

I wish I could give like that more often, but my own concerns about my future and career and carefully crafted image, my insecurities and aches and dark spots, cloud my capacity to give in that way for too long.

photo from flickr.com/brungrrl

Still, in those few moments where I can give as I should, the universe appears right and good and beautiful. It’s hard; it’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever done but also one of the easiest, depending on my state of mind, to give like Jesus gave and still gives. I don’t know if I’ll ever get it consistently right, but it’s not a bad thing to try in this magical time of year, where we celebrate the birth of Christ, the greatest giver of gifts that the world of men has ever known.

Merry Christmas everyone, and may God bless us all!