Religion is often a corporate experience, and that frustrates and saddens me. Sometimes it even leads me to vice. I take responsibility for my choices, but bad religion has been, on more than one occasion, a toxic influence that tipped the scales.

Soon, I want to write about what makes religion corporate, but that’s a tough topic to tackle. If I don’t articulate ideas in a thoughtful and nuanced but principled way, I could do more damage than good, and I don’t want that. To warm up for that discussion, I’ll tiptoe into the topic by looking at specific religious-minded people and things that aren’t corporate in the next few weeks. Today we’re talking about Norman Mailer.

Here’s a quick background for Norman Mailer, in case you aren’t familiar with him: Along with writers like Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion and Truman Capote, he gets credit for developing the New Journalism style, a style that smiles at story-driven techniques in nonfiction work. For his 1979 novel, The Executioner’s Song, Mr. Mailer won a Pulitzer Prize. That’s not why I find him interesting, but I wanted to establish his respect within literary circles before looking at his theology.

I had heard of Norman Mailer in college, but I didn’t go through an entire book of his until this interview that he did with Entertainment Weekly (found here). The interview led me to pick up The Castle in the Forest, a book about the demons who had been assigned to oversee and corrupt Adolph Hitler when he was a child. Suprisingly enough for a modern novel, it’s a book that takes seriously the idea that angels and demons fight for influence over our personal lives and our collective histories. Think C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters with more sex told in context of one history’s greatest villains.

When C.S. Lewis writes about supernatural forces battling for a soul, he can count on the support of his faith-based audiences. (I say that as someone who considers C.S. Lewis to be an excellent, under-rated writer who has had a great influence on my life.) But, when Norman Mailer does it, he is earnestly embracing an idea that his fellow literary contemporaries would mock with condescending sophistication. Doing that takes courage and cojones, and that gets my attention.

In fact, I was so intrigued by the theology and the philosophy found in The Castle in the Forest that I picked up Mailer’s book On God: An Uncommon Conversation to learn more about his religious thoughts. While some of his other books have religious themes, this is the first one that is entirely focused on thoughts about God. I don’t even agree with all of the ideas in it. So why mention him here? Because, believers and unbelievers both need people like Norman Mailer to bridge the gap between the secular and the spiritual camps.

On God has very few quotes or summaries from other theologians or thinkers, and Mr. Mailer begins the book by admitting his limited formal training in theology. Those are both good, uncorporate things. I’ve read too many books that have countless citations but no original thoughts. That happens, I suspect, when the author places more value on what other people think than on what he can discover and observe for himself.

A variation of this is the absurd notion that formal education alone determines someone’s competency in a subject. I’ve met a good number of talented artists, craftsmen, and thinkers who were self-taught, and I’ve known a few exceptionally incompetent people who were formally educated. Sometimes formal education can enlighten and illuminate matters, but other times it merely corrupts and clones carbon-copies of the teacher overlords. Why do you think so many theologians, scientists, or English professors share nearly identical opinions about almost everything?

There’s no formulaic rehashing of well-known theologies in Mr. Mailer’s book. Instead he weaves all of his experiences together into an imaginative theological quilt that doesn’t whitewash the evil that men can do, nor does it hide doubts.

Plastic, a tool of the Devil meant to turn our attentions away from solid, lasting things and toward a disposable mentality according to Mr. Mailer, makes its way into his theology. So does bureaucracy: it can tie up the resources of heaven, giving the Devil a temporary advantage. So too does the Enlightenment: a time that Mr. Mailer praises for the scientific advancements but condemns for the way it anointed reason the supreme king of our time.

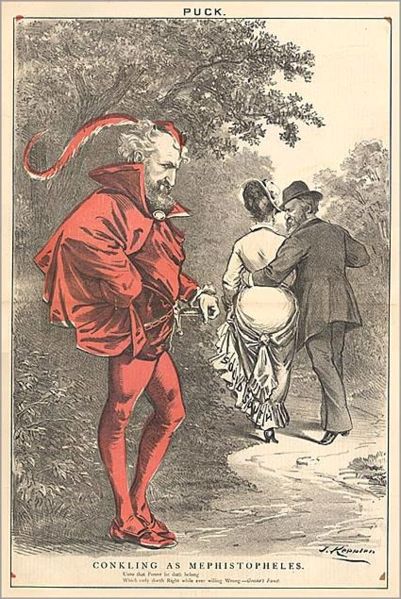

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump by Joseph Wright

Norman Mailer may be accused of many things, but I can’t imagine any sensible person would accuse him of having a faith that is fragmented and inconsistent with his life and his work. People who do not bring all of themselves into the things they advocate tend to produce corporate results. It’s what happens when a salesperson tries to sell you on something that he doesn’t value. It’s why the work of an uncommitted dilettante artist is rarely compelling. It’s not what Norman Mailer or any good writer does.

When a religious leader advocates a principle that doesn’t mesh with how he lives his life, then corporate religion results. That’s not the same thing as advocating an ideal that you yourself struggle to meet if the struggle to live up to an ideal is part of your theology. Norman Mailer is no saint: he stabbed his second wife with a pen, perhaps with an intent to kill. But in his theology he sees souls as an ever-shifting mix of good and evil, a percentage that can change based on the things we do, so his own life fits into that scheme.

In Mailer’s theology, there is something good even in a mostly vile soul, and there is a sliver of corruption and darkness even in a saint. This kind of nuanced perception of things is more precise, but it involves extra effort to individualize, and that’s not something corporate people do.

One of the boldest ideas in the book is Mr. Mailer’s claim that God is not all powerful or all good and that the ultimate triumph of good over evil is not a guaranteed thing. How else to explain a Holocaust, he argues. I disagree with that conclusion. In my way of seeing things, the ability to love is possible only with an ability to choose what and who to love, and that love is such a defining quality of God and of goodness in general that God would cease to be fully good if He deprived us of our ability to make choices or to face the consequences of those choices.

Still, I admire the sense of mystery that Norman Mailer promotes. He doesn’t claim to have all the answers. That’s what corporate people do. Instead he encourages us to do our best moment by moment, listening to our hearts and to God’s promptings about the good we should do in the moment. That’s advice I can wholeheartedly embrace, even though I don’t agree with everything he says. Likewise, I don’t expect you to agree with everything I have to say. Just listen to heart about the things that are true and the things that aren’t. If you really want to know, you’ll know what’s right for the moment at hand, but be careful because it may not be what you want to hear.

I can’t be entirely sure about this, of course, but I suspect that in the grand scheme of things, it’s much more important to do what’s right and good in the moment than to get the theology exactly right while ignoring the dictates of the moment. How about you?

Thanks for reading and God bless.